APIA Every Day is our commitment to learning and sharing about historic places significant to Asian & Pacific Islander Americans, every day.

Follow Us →

Day 310: Portland Rizwan Mosque, Portland, Oregon

📌APIA Every Day (310) - The Portland Rizwan Mosque, built in 1987, is a local chapter of the international Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in India, the Ahmadiyya Mission first spread to the United States in the 1920s, as Ahmadi Muslim immigrants sought refuge from persecution. As the first mosque built in Portland, the Rizwan Mosque quickly became an important multiethnic religious center for the city, serving the local Muslim community for decades.

The roots of the Portland Ahmadiyya Muslim community trace back to Pakistani and Indian university students and professionals who settled in Oregon during the 1960s. This small group gathered at various residences to pray and commemorate Islamic celebrations with no regard to sectarian differences. In 1966, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community of Portland was officially incorporated. As the local Muslim community grew, gaining more South Asian and African American members, services were held at locations such as the St. Pius X Church and the Jenkins Estate. Eventually in the 1980s, as the need for a formal worship space became clear, two doctors initiated fundraising efforts to build a mosque.

In 1985, with permission from the Ahmadiyya Community, the congregation purchased land in a residential neighborhood of Portland for its future religious center. Two years later, in 1987, the Portland Muslim community gathered to celebrate the placement of the mosque’s first foundation stone. Later that same year, the building was dedicated in a ceremony attended by the Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Mission, inaugurating the Rizwan Mosque as an official branch of the Ahmadiyya movement. The mosque’s design blended traditional Islamic features, like a tall minaret, with the style of typical American suburban architecture.

Today, the Portland Rizwan Mosque serves a culturally diverse congregation which is primarily South Asian but also includes Southeast Asians and African Americans. The mosque continues to hold daily services and, like other Ahmadiyya centers across the country, organizes various social programs and community outreach events. One of the most significant of these programs is Open Mosque Day, an annual event during the holy month of Ramadan where neighbors are invited to join the congregation for Iftar and learn about Islam.

Day 309: Honpa Hongwanji Hawai’i Betsuin, Honolulu, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (309) - The Honpa Hongwanji Hawai'i Betsuin in Honolulu, dedicated in 1900, is part of a larger religious organization called the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai'i. As one of the earliest Buddhist temples on the Islands, the Betsuin was built a decade after the establishment of Hawai'i’s first Buddhist temple in Hilo. For nearly 125 years, the Honolulu Betsuin has served as the flagship temple for the Hongwanji Mission in Hawai’i and continues to be a significant proponent of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in the United States.

The Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai’i was initially founded in the late 19th century by Reverend Soryu Kagahi who was concerned about the spiritual well-being of Japanese immigrants who had become disconnected from temples in Japan. During his visit to Hawai’i, Rev. Kagahi founded Buddhist communities on Hilo and Honolulu, establishing the Hilo Betsuin in 1889. Following Rev. Kagahi’s initiatives, Bishop Honi Satomi began growing Honolulu’s congregation in 1898. Together with his nephew, Reverend Yemyo Imamura, he constructed a temple building on Fort Lane in 1900. A year after its dedication in 1901, the Honpa Hongwanji Hawai’i Betsuin in Honolulu hosted Queen Lili’uokalani and Mary Robinson Foster for a memorial service. This visit had a profound effect on the local Buddhist community, encouraging more members to join the congregation.

With a growing community, construction on a new temple building began in 1916 and was completed in 1918. The design of the temple blended traditional Indian aesthetics with more contemporary Western architecture, honoring the historic roots of Buddhism while also acknowledging its universality. In order to garner greater acceptance among Americans, the interior was designed with a church-like layout, featuring wooden pews, a pulpit, and an organ. This style would influence nearly 75 percent of all Buddhist temples built in Hawai’i after the 1940s as they continued to follow this precedent. Around this time, the Honolulu Hongwanji temple received its honorary title of “Betsuin” from the main temple in Japan and was recognized as the headquarters of the Hawai’i Hongwanji Mission.

In the mid-20th century, the Honolulu temple began a series of expansions, including the addition of a mausoleum to the main hall. However, during World War II, construction plans were put on hold, and many Buddhist ministers were incarcerated while temples across Hawai'i were closed. After reopening in the post-war period, the Hongwanji Mission founded a Hongwanji Mission School near the Honolulu Betsuin complex in 1949. In 1964, a townhouse and annex temple, which included a large social hall, were added to house students and the Buddhist Women's Association.

Today, the Honpa Hongwanji Hawai'i Betsuin continues to serve an active congregation while overseeing 30 Hongwanji temples across Hawai'i. Services at the Betsuin are held every Sunday in both English and Japanese, and the temple organizes educational programs, cultural activities, and festivals throughout the year. However, like most other Buddhist temples across the state, the Honolulu Betsuin has faced issues of declining membership. Between 2007 to 2021 alone, the temple’s congregation diminished by 52 percent. To combat this decline, the Betsuin has committed to diversifying its available programs to attract new members. With money from the National Fund for Sacred Places, the temple is set to modernize its community spaces, ensuring accessibility for future generations.

Day 308: Iosepa Settlement Cemetery, Iosepa, Utah

📌APIA Every Day (308) - The Iosepa Settlement Cemetery, established circa 1889, is located in a ghost town in Utah’s Skull Valley. Originally a 1,920 acre ranch, the Iosepa area was settled in the late 19th century by Pacific Islanders, predominantly Native Hawaiians, who had immigrated to the United States after converting to Mormonism. Today, the cemetery stands as one of the last surviving sites documenting the early Polynesian history of Utah.

In the 1850s, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began sending missionaries to Hawai’i and the surrounding Pacific Islands. One of the most influential figures in this missionary effort was Joseph F. Smith, the eventual namesake for Iosepa. In 1889, about 50 Native Hawaiians had joined the church and migrated to Salt Lake City. However, due to discrimination against the new arrivals, the Church relocated the community to Skull Valley. Once settled in Iosepa, the Native Hawaiians established a small town following a gridded plan typical of Mormon settlements. At the center of the town, they built a church and schoolhouse in a public square (called an imilani), with other buildings lining two main streets named Honolulu and Kula. The Iosepa Cemetery was founded as early as 1889, the same year as the settlement’s establishment, when the first burial took place. Over time, Iosepa grew to encompass 226 people and community members continued to preserve their heritage through cultural traditions like lu’aus.

Throughout this period, the Polynesian residents worked as laborers on farms under the Iosepa Agricultural and Stock Company. By 1908, the community had created an elaborate irrigation system and grown numerous fruit trees on residential properties to guard against the harsh Utah summers. Two years following these improvements, the town gained greater financial independence and an increased quality of life. In 1915, as the Mormon Church began construction on a temple in Hawai'i, many Iosepa residents opted to move back to the Pacific Islands by 1917. Those who remained continued to be buried at the Iosepa cemetery, with burials occurring as recently as 2019. As the town was abandoned, a livestock company purchased the land and demolished most of the buildings, leaving only the cemetery and a few stone foundations behind.

In 1971, the Iosepa Settlement Cemetery was added to the National Register of Historical Places, in recognition of its significance to Polynesian history in Utah. A century after the town’s establishment, a historic marker was dedicated at Iosepa by the Mormon Church President Gordon B. Hinckley in 1989. Although the town no longer has any permanent residents, Pacific Islander continue to visit the site annually to honor their pioneer ancestors with lu'aus. To accommodate these visitors, the Iosepa Historical Association added a pavilion with a stage, kitchen, and restrooms to the site. Currently, the Association is gathering donations to update the existing facilities, ensuring that future gatherings commemorating Iosepa continue to occur.

Day 307: Jain Society of Greater Detroit, Farmington Hills, Michigan

📌APIA Every Day (307) - The Jain Society of Greater Detroit (JSGD) was initially founded by a group of Indian Jain professionals who had immigrated to the United States following the Immigration Act of 1965. Many of these early members, who settled in the Detroit Metropolitan area, were primarily students pursuing higher education at American universities. In 1998, the JSGD established the first Jain temple in Detroit in the city’s suburb of Farmington Hills. This temple quickly became a significant gathering space for the Indian Jain community across the state.

The origins of the JSGD trace back to 1975, when a small congregation of just nine people began gathering at each other's homes in Taylor, Michigan, to observe religious holidays. By the end of that same year, the congregation had grown to 50 families, prompting the move of worship services to a local community center and church hall. In 1981, the Society was officially incorporated and in the coming years, established various ongoing community programs like an annual summer camp and religious school. In 1985, the Detroit Society hosted the third national Jain Convention of North America, inviting Jains from across the country to participate in workshops and lectures highlighting their shared heritage.

In 1989, the JSGD acquired three acres of wooded property in Farmington Hills for a future temple. Four years later, they purchased an adjacent three-acre lot with an existing house, which became a temporary religious center. Construction of the formal temple began in 1995 and 160 Jain families gathered in 1997 to perform a brick laying ceremony. In 1998, the JSGD held a ten-day Pratishtha Mahotsav ceremony to consecrate the completed building. The new temple included a prayer hall, a social hall, a kitchen, a library, and classrooms, with a distinctive marble shikhara (temple dome) on its exterior imported from India.

Currently, other than the Hindu-Jain Bharatiya Temple in Lansing, the JSGD Temple in Detroit is the only major Jain temple in the state. With a congregation of over 700 families, it continues to host weekly worship services and offers study classes for both youth and adults. In 2023, the JSGD celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Jain Center, an event attended by over 1,000 people, including Deputy Mayor of Farmington Hills Randy Bruce. During the celebration, the community raised $500,000 for the current temple’s expansion, reflecting the JSGD’s growing significance in the Detroit area.

Day 306: Anzen (Teikoku Company), Portland, Oregon

📌APIA Every Day (306) - Anzen, previously known as the Teikoku Company, was Portland’s oldest Japanese grocery and retail store. Initially established in Japantown (Nihonmachi) by Mosaburo Matsushima in 1905, it remained an essential shopping destination for the local Japanese community for over a century. Although Anzen moved from its historic location in the Merchant Block in the mid-1940s, the building still stands as a testament to early Japanese American history in Portland today.

Mosaburo Matsushima, who immigrated to Oregon from Okayama, Japan, originally opened his store under the name Matsushima Shoten. In 1911, six years after opening, Matsushima renamed his business the Teikoku Company, stocking a variety of goods for Japanese laborers, including canned food, hats, and caulk boots. At the same time, the shop became an agent of Yokohama Bank enabling Japanese immigrants to send money to their families in Japan. In the 1920s, Matsushima’s nephew and son, Umata Yasui Matsushima and Ayao Matsushima, took over the store’s management. During this time, the family inhabited and maintained the Merchant Hotel (then known as the Teikoku Hotel), which operated on the floors above the store and served as a boarding house for immigrants.

In the 1940s, Umata assumed full control of the business as the rest of the family returned to Japan. Aside from managing the storefront in Portland, he also traveled throughout the Pacific Northwest, delivering goods to Japanese laborers working in canneries and lumber camps. In 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Portland officials began closing Japanese-owned businesses around the city. Umata, in his position as the owner of the Teikoku Company, was arrested and sent to various detention centers around the country. The store was closed and his wife Fumi and their two children were incarcerated at the Minidoka Camp in Idaho.

After returning to Portland in 1946, the Matsushima family reopened their business near its original Japantown location. Due to concerns over the name “Teikoku” (which translates to “imperial”), the city government prohibited them from reopening under the same name. Instead Umata established the new store as Anzen, a word meaning “safety.” In 1968, Anzen moved to a new location in Portland's Lloyd District. Umata's sons, Yoji and Hiroshi, took over the business, continuing to sell Japanese foods, home goods, medicine, and books.

In 1975, the Merchant Hotel, the original location of the Teikoku Company Store, was added to the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Portland Skidmore/Old Town Historic District. In 2014, after 109 years of operation, Yoji and Hiroshi Matsushima retired, and Anzen closed its doors. Although Anzen is no longer in business today, its legacy is embodied at the site of the original Teikoku Company which is now home to Goodies Snack Shop, an Asian food store established in 2022. While this marks a new beginning for the historic Merchant Building, Anzen continues to be remembered as a beloved community shopping destination by the Portland community.

Day 305: Kochiyama House, Harlem, New York City, New York

📌 APIA Every Day (305) - The Yuri Kochiyama House in Harlem, New York City, is a historically significant site located at 168 W 126th Street, in the heart of one of America’s most influential cultural and political neighborhoods. Harlem, known for its deep connections to the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power Movement, and artistic renaissance periods, became home to Yuri Kochiyama and her family in the 1960s. Situated near key landmarks such as the Apollo Theater and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Kochiyama House served not only as a family residence, but a robust hub for radical grassroots political organizing. The location placed Kochiyama at the crossroads of major social justice movements, allowing her to engage with activists, intellectuals, and organizers working to advance racial and economic justice. The physical structure of the house itself may appear unassuming, but its historical significance stems from the transformative activism that took place within its walls.

Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American activist who had been incarcerated in a World War II incarceration camp, dedicated her life to fighting for civil rights, labor justice, anti-imperialism, and Black liberation. After moving to Harlem, she became deeply involved in grassroots organizing, supporting movements for Puerto Rican independence, reparations for Japanese American incarceration histories, and justice for political prisoners. She famously worked alongside Malcolm X, whom she met through Harlem’s activism networks, and was present at the Audubon Ballroom when he was assassinated in 1965. The Kochiyama House became a meeting place for activists and a site for radical political discussions, where community members organized efforts against systemic oppression. Her work in Harlem bridged struggles between Black, Asian, and other marginalized communities, making her home a key symbol of solidarity and resistance.

Today, there are ongoing efforts to preserve the historical legacy of the Yuri Kochiyama House and ensure her contributions to activism and the Harlem community are remembered such as painting murals in her honor. The Kochiyama house is often highlighted in walking tours and educational programs focused on Harlem’s radical history. While the house itself remains a private residence, its significance as a gathering place for civil rights struggles underscores the importance of preserving such spaces that connect past movements to present-day social justice efforts.

Day 304: Historic Chinatown, Detroit, Michigan

📌 APIA Every Day (304) - Detroit, Michigan, has had two distinct Historic Chinatowns. The first Chinatown was established in the early 20th century along Third Avenue and Michigan Avenue, near downtown Detroit. This area became a cultural and economic hub for Chinese immigrants. However, due to urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s, many residents and businesses were displaced, leading to the development of a second Chinatown in the 1960s, located along Cass Avenue near Peterboro Street. This newer Chinatown served as the center of the Chinese American community for several decades, but with continued urban redevelopment and much of the Chinese population dispersal to suburban areas such as Madison Heights and Troy, it too saw a decline by the late 20th century. Today, remnants of Detroit’s Chinatowns can still be seen in the architectural elements and signage that remain in these respective neighborhoods.

Chinese immigrants established small businesses beginning in the early 1900s, primarily laundries and restaurants, in order to sustain their newly resettled lives in Detroit. Despite facing racial discrimination and exclusion from many industries, the Chinese American community in Detroit maintained a strong sense of cultural identity and solidarity. The growth of the automobile industry in the early 20th century attracted more Chinese immigrants, along with other Asian ethnicities, to the city.

Efforts to preserve the history of Detroit’s Chinatowns are ongoing, as community organizations, leaders, and state representatives collaborate to maintain what little is left of Detroit’s Chinatown. In recent years, there have been initiatives to install historical markers and restore significant buildings in the Cass Corridor area to acknowledge the contributions of Chinese immigrants to Detroit’s urban development. For example, in summer 2024, one million dollars in the state’s budget was earmarked to preserve Chinatown community infrastructure and histories.

Day 303: Agaña Historic District, Hagåtña, Guam

📌 APIA Every Day (303) - The Agaña Historic District, located in the capital city of Hagåtña, Guam, is a significant cultural and historical area that reflects the island’s diverse past. The district itself is composed of several historically significant structures, including Spanish-era buildings, remnants of pre-colonial CHamorro settlements, and American-era infrastructure. The 2-acre Historic District consists of the following five buildings: the Calvo-Torres, Rosario, Martinez-Notley, Lujan and Leon Guerrero houses. These five buildings are some of Guam’s oldest standing buildings and represent how the island has changed over time.

The history of the Agaña Historic District is deeply intertwined with Guam’s broader history, which spans thousands of years and includes Indigenous CHamorro society, Spanish and American colonialism, as well as Japanese occupation during World War II. Before European contact, the area that is now Hagåtña was a significant settlement for the CHamorro people, who established fishing and agricultural communities. In the 17th century, Spanish colonizers made Hagåtña the capital of the Marianas, introducing Christianity and European architectural influences. Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, Guam became a U.S. territory, and Hagåtña evolved under American administration. During World War II, the now-Historic District suffered extensive destruction due to Japanese occupation and subsequent U.S. military bombardment during the island’s liberation in 1944. The post-war reconstruction reshaped Hagåtña, but remnants of its colonial past remain as a testament to its historical significance.

In 1985, the Agaña Historic District was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places. Restoration projects focus on revitalizing Spanish-era structures, maintaining Indigenous CHamorro architectural elements, and promoting overall public awareness of the area’s historical significance in the context of Guam’s history. Community engagement programs, heritage tours, and educational initiatives further contribute to preservation efforts by fostering appreciation and understanding for the district’s legacies.

Day 302: Syriatown, Boston, Massachusetts

📌 APIA Every Day (302) - Boston's Little Syria, also known as Syriatown, was a vibrant immigrant enclave that flourished between the 1880s and 1950s. Located in the areas now encompassing Chinatown and the South End, this neighborhood became home to a significant population of Arabic-speaking immigrants from the SWANA (Southwest Asian North African) region, notably Syria and Lebanon. Centered around streets like Hudson Street and Tyler Street, the Syrian community established a rich cultural and economic presence characterized by bustling businesses and textile industries, peddling economies, religious institutions, and social organizations that reflected their Arab heritage.

The formation of Little Syria was closely linked to the wave of immigration from the Ottoman province of Greater Syria during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Seeking better economic opportunities and escaping political unrest, many Syrians and Lebanese settled in Boston, attracted by the city's industrial growth and economic opportunities. Among the notable figures was Hannah Sabbagh Shakir, a Lebanese-American businesswoman who co-founded the Syrian Ladies' Aid Society of Boston in 1917. This organization played a crucial role in supporting immigrants by providing essential services and building community.

While much of the physical landscape of Syriatown has been demolished due to urban renewal and the expansion of Boston’s Chinatown, public history-based preservation efforts ensure that the contributions of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants remain an integral part of the city’s immigration histories. The Boston Little Syria Project, a public history initiative, aims to preserve the little-known history of this once-thriving neighborhood through walking tours, exhibitions, and collaborations with local organizations such as universities and historical associations.

Day 301: Honoka’a People's Theatre, Honoka’a, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (301) - The Honoka’a People’s Theatre, located on the Big Island of Hawai’i, was established in 1930 by Japanese immigrant Hatsuzo Tanimoto. At a time when local entertainment catered mostly to single men, the theatre provided a space for families to enjoy live shows and films together. For decades, it served as the cultural heart of Honoka’a, serving as a significant gathering space for Japanese, Filipino, and Native Hawaiian communities on the island to enjoy cultural entertainment.

In the early 1920s, there was a marked period of increased theater construction across the Hawaiian Islands. It was during this time that Hatsuzo Tanimoto initially bought land for the People’s Theatre in 1929. It opened the following year with 650 seats and dedicated spaces for an auditorium and performance stage. Eventually Tanimoto’s son, Christian Yoshimi Tanimoto, took over booking movies and devised a schedule where the theatre showed Japanese films on Mondays, Filipino films on Tuesdays, and family entertainment on the weekends. At this time, Christian and his wife Peggy Tanimoto lived in an apartment above the theatre. Peggy, active in the Honoka’a community, would organize various live performances at the theatre and around town, including classical Japanese dances and Hula presentations.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, following Christian’s death, the People’s Theatre struggled to stay open and went through multiple management changes. After manager James Carvalho retired, Dr. Tawn Keeney, a local physician, leased the theatre in 1982. With Peggy’s passing and the brief closure of the theatre, Keeney bought the property in 1990 and began renovations to restore the aging building. Three years later, the theatre reopened with an updated screen, sound system, and modernized facilities while also retaining its old 35mm film projectors.

In the 2000s, events like the annual Hāmākua Music Festival helped to revitalize use of the theatre, bringing musicians from all over the region to perform. Around this time, Lanakila Mangauil founded a hula halau (hula school) in the building and The Honoka’a Community Theatre Group began writing plays for original live shows. However, in 2014, the theatre faced the possibility of closure as Hollywood shifted away from producing movies in a 35mm film format. In response, over 500 local families raised $120,000 to buy a new digital projector for the auditorium, saving the theatre.

The Honoka’a People’s Theatre was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2015 in recognition of its cultural importance to the local community. Now a 525-seat venue with an expanded stage, it continues to show films, host musical performances, and organize cultural events. Recently in 2024, the theatre screened a documentary highlighting the region’s plantation history during Honoka’a’s inaugural Hāmākua Sugar Days Festival.

Day 300: Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association Building, Portland, Oregon

📌APIA Every Day (300) - The Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) Building was constructed in 1911 in Portland’s New Chinatown District (APIA Every Day 33). Like other CCBA branches across the nation, the Oregon organization was committed to fighting discrimination against Chinese community members and businesses. As a major governing body in Chinatown, the CCBA managed the district’s primary social, educational, and political affairs. The Oregon CCBA building has served as the organization’s headquarters for over a century and has remained a central institution in Portland’s Chinatown from its founding to present day.

Eight years after the first CCBA was formally established in San Francisco, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of Portland formed circa 1890. One of the organization’s earliest initiatives was the creation of the Portland Chinese Language School in 1901—a program that still exists today. As the CCBA grew, community members formed the Chinese Conservative Investment Company in 1910 to raise funds for a new association space. The following year, the Company successfully purchased an empty lot and Chinese laborers constructed the present four-story CCBA Building. Over the next few decades, the building took on the role of an informal city hall and became an important gathering space for the Chinese community. During this era, the president of the CCBA was often referred to as the “Mayor of Chinatown.”

In the 1970s, the CCBA began raising funds for the building’s renovation to update the existing facilities. Around the same time, the organization established the Chinatown Development Committee to help revitalize the entire district. Between 1979 and 1981, the CCBA Building was restored with donations from the Republic of China and the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office. With its updated headquarters, the CCBA and Portland Development Commission turned their attention to reviving Chinatown: installing Chinese street signs, decorative lamp posts, and a Chinese Gateway in the neighborhood during the 1980s.

Recognizing the importance of the CCBA Building in the development of Portland's Chinese community, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Portland New Chinatown/Japantown Historic District in 1989. More than a century after its establishment, the Oregon CCBA continues to support the local Chinese community while also promoting greater appreciation for the Chinatown district. The upper floors of the CCBA Building now house an English-Chinese library and a museum, welcoming visitors to explore the history of Chinese Americans in the area.

Day 299: Thai Xuan Village, Houston, Texas

📌APIA Every Day (299) - Houston’s Thai Xuan Village, founded in 1993, is an apartment complex that has historically been home to the city's Vietnamese community. After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, waves of Vietnamese refugees immigrated to the United States in the 1970s and ‘80s. Many of these immigrants settled around Gulf Coast cities in order to find working class jobs that didn’t require English proficiency. With its rapidly growing Vietnamese population, Houston in particular became home to a number of residential communities like Thai Xuan Village. Over time, these housing complexes became informal community spaces for Vietnamese refugees to connect and preserve their shared culture.

The Thai Xuan Village complex was originally constructed in 1976 under the name of Cavalier Apartments. Father John Chinh Tran, a Vietnamese Catholic priest, later bought the complex in 1993 and renamed it Thai Xuan after his old village near Saigon. Tran invited local Vietnamese refugees to occupy the building and units of the complex were sold as condominiums in 1966. During the next 15 years, the complex faced issues of proper maintenance as the building conditions deteriorated. Following complaints from neighboring community members, city officials threatened the complex with demolition in 2007. In response, the residents formed a tenant organization and successfully raised $250,000 for building repairs over a period of two years.

Safe from demolition threats, Village residents continued to cultivate a dynamic community space. Over the years, former apartment units functioned as hair salons, schools, and stores selling basic necessities. Microfarms growing various Vietnamese fruits and vegetables began springing from fenced yards and balcony spaces. In the complex’s courtyards, both a Virgin Mary statue and Buddhist shrine were dedicated to serve the community’s primary religious affiliations.

Three decades after Father Tran’s arrival, Thai Xuan Village remains a lively apartment complex today, housing as many as 1,000 individual residents. A testament to organic community-building, the Village represents the Houston Vietnamese population’s success in fostering a sense of belonging in an unfamiliar country.

Day 298: Portland Vedanta Society, Portland, Oregon

📌APIA Every Day (298) - The Vedanta Society of Portland was established in 1925 and its first informal temple was dedicated in 1934. The society is one branch of a larger religious organization that was originally founded in New York by Swami Vivekananda in the late 19th century. The Portland society would eventually organize efforts to dedicate a formal temple on a rural property in the neighboring city of Scappoose in 1954—constructing the first official Vedic temple in the Pacific Northwest.

Swami Prabhavananda, the founder of the Vedanta Society’s Portland chapter, immigrated to the U.S. from India in 1923. Initially assisting the Vedanta Society of San Francisco (APIA Every Day 110), he moved to Oregon in 1925 and held public lectures discussing Vedantic philosophy. Prior to having an established temple space, these lectures and meetings would be held in various buildings around Portland. It wasn’t until 1934, following the arrival of Swami Devatmananda in 1932, that the first permanent location for the society was purchased near the city’s Hillside neighborhood. It was also around this time that the society acquired its 120-acre property in Scappoose for its future Retreat property: otherwise known as the Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama. Once a clear-cut lot, volunteer labor over the years from society members transformed it into a lush forested trail.

In 1943, on the 50th anniversary of the Vedanta Movement in America, the Portland society moved from its old temple house to a new property near Portland State University. In the same decade, construction on the Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama Temple in Scappoose was underway and completed in 1954. When Portland State University claimed the society’s old meeting space for an expansion project, the present center in Portland’s Mt. Tabor neighborhood was purchased and dedicated in 1968. The existing single-family home on the site was remodelled to accommodate a central worship space, a library, and classrooms.

Since its initial foundation a century ago, the Vedanta Society of Portland remains active today, hosting religious services, organizing youth forums, and offering spiritual lectures at its main Portland location. Members also continue to participate in festivals like the annual Interfaith Celebration on July 4th at the society’s Retreat location in Scappoose. In 2020, an adjacent 169 acres of land at the Ashrama location was purchased by the society, leaving room for future expansion.

Day 297: The Garnier Building, Los Angeles, California

📌APIA Every Day (297) - The Garnier Building, constructed in 1890, is the oldest remaining building from Los Angeles’ original Chinatown district and the oldest surviving historic Chinese structure in a major city of California. The building was an important political, economic, and social center for the local Chinese community for much of the early 20th century. Serving as the early headquarters of organizations like the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), it was informally regarded as the old Chinatown district’s city hall.

The Garnier Building was originally constructed by a French businessman, Philippe Garnier, and was designed primarily for Chinese business tenants in the area. A collection of various Chinese associations, businesses, religious spaces, and schools were located inside. The building's layout reflected traditional Chinese spatial hierarchies, with spaces of authority placed on the upper floors, closer to the heavens. Following this idea, churches and schools were located on the second story while the ground floor was occupied by commercial spaces. Aside from the CCBA, other notable tenants included The Chinese American Citizens Alliance, the Sun Wing Wo Company merchandise store, and The Wong Ha Christian Chinese Missions School. Many of these establishments are still active in Los Angeles today.

Once it was occupied in the 1890s, Chinese tenants remained continuous inhabitants of the building for a period of six decades until the 1950s. Beginning in 1933, the Los Angeles city government started evicting Chinese Americans from the old Chinatown district in the interest of advancing transportation developments like the construction of Union Station. Demolishing much of Chinatown in the process, only the Garnier Building was left standing. In the 1950s, however, the southern half of the building was torn down to accommodate the new Hollywood/Santa Ana freeway. In the aftermath, the building was largely abandoned.

In acknowledgment of the Garnier Building’s significance to the early Chinese community and the city’s old Chinatown, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 as part of the Los Angeles Plaza Historic District.In 2003, after 20 years of community planning and activism, the Chinese American Museum (CAM) officially opened in the vacant building. The first institution of its kind in Southern California, the CAM continues to preserve and highlight the historical legacy of Chinese Americans in Los Angeles.

Day 296: Glad Day Bookshop, Boston, Massachusetts

📌 APIA Every Day (296) - Glad Day Bookshop, though primarily known as the oldest LGBTQ+ bookstore in North America with its origins in Toronto, played a crucial role in developing Boston’s queer Asian community. Located in downtown Boston on 43 Winter Street, during the late 20th century, the bookstore served as more than just a retail space—it became a gathering place for marginalized groups seeking representation and community. They relocated the bookstore because the initial location on 22 Bromfield Street ended up being destroyed by acts of homophobic violence. Situated in an era when queer Asian Americans faced both racial and sexuality marginalization, the Glad Day Bookshop provided a rare and affirming environment where individuals could find literature, resources, and connections tailored to their intersectional identities.

The history of Glad Day Bookshop in Boston is deeply intertwined with the rise of LGBTQ+ activism and the formation of identity-based organizations. In the 1980s and 1990s, as the queer rights movement gained momentum, many Asian Americans in the queer community struggled with dual forms of invisibility—within broader Asian American spaces that often upheld traditional values around gender and sexuality as well as within mainstream LGBTQ+ circles that were predominantly white. The bookshop became a crucial space for addressing these challenges, offering books by and about queer Asian voices, hosting discussions, and connecting individuals who felt isolated. Over time, it served as an incubator for advocacy, helping to inspire the formation of the group, Boston Asian Gay Men and Lesbians (BAGMAL) in 1979, dedicated to building out a community that met the specific needs of Boston’s emerging queer Asian population. BAGMAL ran a newsletter series and organized many social events around the queer Asian identity in the Boston area. The organization continues to exist today, although in a much smaller capacity.

The significance of Glad Day Bookshop extends beyond its role as a bookstore; it was a catalyst for cultural and political change. Creating a space where queer Asian individuals could see themselves represented in literature, it helped validate and empower their identities. While the bookstore itself may no longer exist in Boston, its legacy lives on in the ongoing fight for intersectional representation and inclusion within both the LGBTQ+ and Asian American communities, as well as social movements. Given that this bookstore no longer exists today, how might historic preservation practices expand to include queer Asian American and Pacific Islander histories, where LGBTQ+ sites important to queer history often faced threats of displacement from urban renewal projects and were targets for homophobic violence.

Day 295: Little Saigon, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

📌 APIA Every Day (295) - Philadelphia's Little Saigon is located in the heart of South Philadelphia, specifically in the neighborhood of Passyunk Square. This vibrant neighborhood is home to one of the largest Vietnamese communities on the East Coast, known for its bustling markets, authentic restaurants, and cultural institutions that reflect the heritage of its residents. The area is a dynamic commercial corridor featuring Vietnamese-owned businesses, including mall plazas, grocery stores, and restaurants, which serve as cultural anchors for both the local Vietnamese American population and the broader Philadelphia community.

The development of Little Saigon is closely tied to the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees following the Vietnam War. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, thousands of Vietnamese refugees arrived in the United States, many of whom passed through resettlement centers like Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania (APIA Every Day 104). Over time, Philadelphia became a preferred destination due to its affordability and the availability of jobs in manufacturing and small business sectors. By the 1980s and 1990s, the Vietnamese community had firmly established itself along Washington Avenue, transforming the area into a thriving cultural and economic hub that continues to grow today.

Efforts to preserve the historical and cultural significance of Little Saigon have been ongoing through community advocacy. Community organizations and artists have worked to document and celebrate the neighborhood’s heritage through oral histories, cultural festivals, and other place-based initiatives aimed at anchoring the Vietnamese diasporic community in Philadelphia. More recently, residents and activists organized for the protection of the ethnic enclave from gentrification and displacement, ensuring that Little Saigon’s presence remains visible.

While Little Saigon has evolved over the past few decades, these community-led preservation efforts continue to highlight the importance of recognizing and safeguarding its role as a center for Vietnamese American identity in Philadelphia. Given that Southeast Asian refugee communities like Vietnamese Americans in Philadelphia have settled in the past forty years, we reflect on whether and how historic preservation practices are prepared to recognize these neighborhoods as significant narratives of larger American historic landscapes.

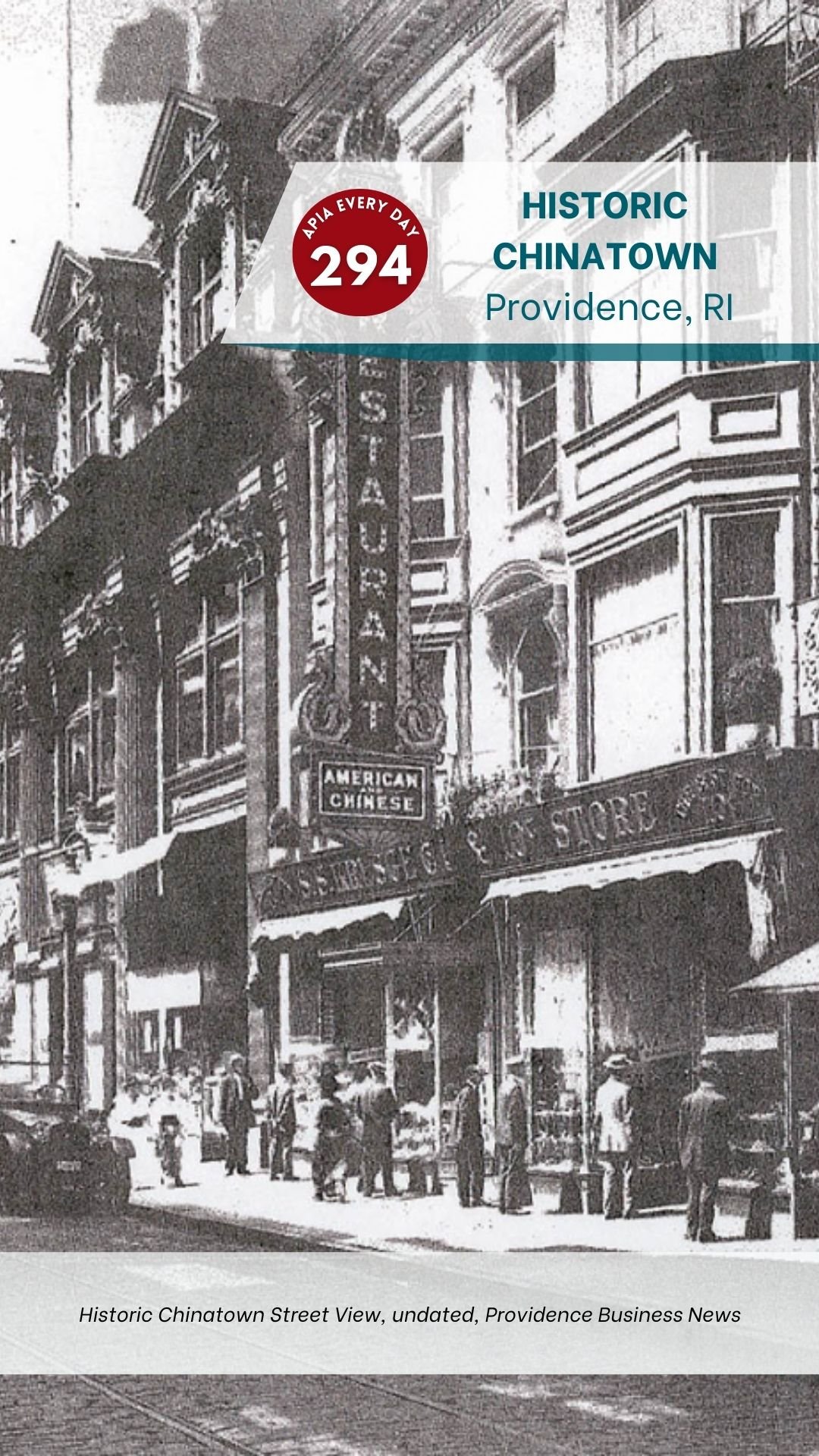

Day 294: Chinatown, Providence, Rhode Island

📌 APIA Every Day (294) - Providence’s Historic Chinatown was a small but significant immigrant community located in the downtown area near Empire and Westminster Streets. Established in the late 19th century, this enclave emerged as Chinese immigrants, many of whom had initially arrived in the United States to work on the railroads and in mining, moved eastward in search of new opportunities and escape harsh racial violence. Providence, a thriving industrial city at the time, attracted Chinese laborers who found work in laundries, restaurants, and small businesses. Unlike larger Chinatowns in cities like San Francisco, New York, and Boston, Providence’s Chinatown remained relatively small, but it served as an essential hub for Chinese immigrants in Rhode Island and the surrounding New England region.

The history of Chinatown in Providence reflects broader patterns of Chinese immigration and exclusion in the United States. The first Chinese immigrants began settling in the city during the 1880s, despite growing anti-Chinese sentiment and restrictive immigration laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The community developed a network of businesses, social organizations, and mutual aid societies that provided support to residents facing discrimination and economic hardship. However, by the early 20th century, Chinatown began to decline due to increasing legal restrictions, racial hostility, and urban development projects that displaced Chinese-owned businesses. By the mid-20th century, much of Providence’s Chinatown had disappeared, with its former residents dispersing to other areas or assimilating into the broader population.

Although Providence’s Chinatown is no longer a distinct neighborhood, its historical significance remains. It was one of the earliest Chinese communities in New England, contributing to the region’s cultural and economic diversity. The Chinese-American presence in Providence helped shape the city's culinary landscape, introducing Chinese cuisine to Rhode Islanders long before it became mainstream in American culture.

The alleyway between Empire and Walnut Street in downtown Providence is the only infrastructure to remain from the former Chinatown neighborhood. Today, efforts to recognize and preserve the history of Providence’s Chinatown continue, with universities, artists, and community organizations spearheading creative public history initiatives that restore this overlooked chapter in Providence’s immigrant history. Given that Providence Chinatown history has largely been forgotten, how might historic preservation practices expand to include Asian histories where, instead of officially designated Chinatowns, small, dispersed Chinese communities existed and contributed to local economies and culture?

Day 293: Little Syria, New York City, New York

📌 APIA Every Day (293) - Once a thriving immigrant enclave in Lower Manhattan, Little Syria was located along Washington Street, stretching roughly from Battery Park to Rector Street. This neighborhood emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a center for Arab immigrants from the SWANA (South West Asian North African) region who were escaping economic hardship and seeking new opportunities in America. Situated near the bustling docks of the Hudson River, Little Syria was well-placed for new arrivals who found work as merchants, peddlers, and factory workers. The neighborhood’s proximity to other immigrant communities, including Irish and Italian enclaves, made it a melting pot of cultures in New York City’s rapidly expanding urban landscape.

The history of Little Syria is deeply tied to the waves of SWANA immigration that began in the 1880s. Many of its residents were Christians fleeing the Ottoman Empire, though Muslim and Jewish immigrants also settled in the neighborhood. The community quickly became known for its vibrant commercial and cultural life, with numerous Arabic-language newspapers, bookstores, coffeehouses, and textile shops. However, by the mid-20th century, much of Little Syria was lost due to urban renewal projects, including the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in the 1940s and, later, the development of the World Trade Center in the 1960s. As a result, many families relocated to other parts of the city, particularly Brooklyn and New Jersey, displacing the once-tight-knit community.

Little Syria left a lasting historical and cultural legacy in New York City despite its physical disappearance. One of its most enduring contributions was the establishment of Arabic-language journalism in the United States, shaping early Arab-American discourse. The neighborhood was also home to prominent figures like the writer and poet Kahlil Gibran, whose work The Prophet remains one of the most celebrated books in modern literature. While most of the original buildings have been demolished, three buildings remain, specifically the St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church, which serves as a rare architectural link to the once-thriving community. In 2009, St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church won landmark status from New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. The other two remaining buildings of Little Syria include the tenement building located on 109 Washington Street and the Downtown Community House, which previously housed a medical center, a nursery, and a library. Today, efforts by historians and preservation organizations such as the Washington Street Historical Society continue to raise awareness of Little Syria’s importance in shaping New York’s diverse immigrant history.

Day 292: Arizona Buddhist Temple, Phoenix, Arizona

📌APIA Every Day (292) - The Arizona Buddhist Temple, with congregational roots in 1933, is the oldest Buddhist temple established in the state. Founded by Japanese Americans who migrated from California to work on farms around Phoenix, the temple follows the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism. Through times of racial strife and discrimination in the 20th century, the temple served as a social and cultural haven for Arizona’s Japanese American community.

Before establishing a permanent worship space, Reverend Hozen Seki—a Buddhist minister from Los Angeles—conducted the congregation’s earliest services on Hitoshi Yamamoto’s farm in Glendale. Many of the temple's enduring social programs, including the Sunday school, annual Obon festival, and Fujinkai (women's organization), were established during this time. In 1936, the community constructed and dedicated a formal temple building in Phoenix. Due to Arizona's Alien Land Laws, the first-generation Japanese American community members (issei) had to purchase land through their citizen children (nisei). The temple site encompassed both a hondo (worship hall) and living quarters for the Reverend and his family.

During World War II, the temple remained closed as Japanese Americans were forced into incarceration camps, though many continued their religious practices within Arizona's detention centers. In 1945, the temple reopened with the return of Rev. Seki and the Phoenix Japanese community. During this time, the temple offered temporary housing and social assistance to community members who had lost their homes and businesses during incarceration. In 1957, when an accidental fire destroyed the temple, temporary services were held in barracks relocated from the Gila River Detention Center. In 1961, a new temple complex was completed south of the original location, featuring a hondo, residential quarters, and classrooms.

In 2024, the temple celebrated its 90th anniversary and commemorated the resilience of the Phoenix Japanese American community. Though the congregation remains active, there are concerns over its aging membership and potential future decline. Despite these challenges, the temple community continues to persist, now offering services in English instead of Japanese to welcome younger generations and new outside members to the congregation.

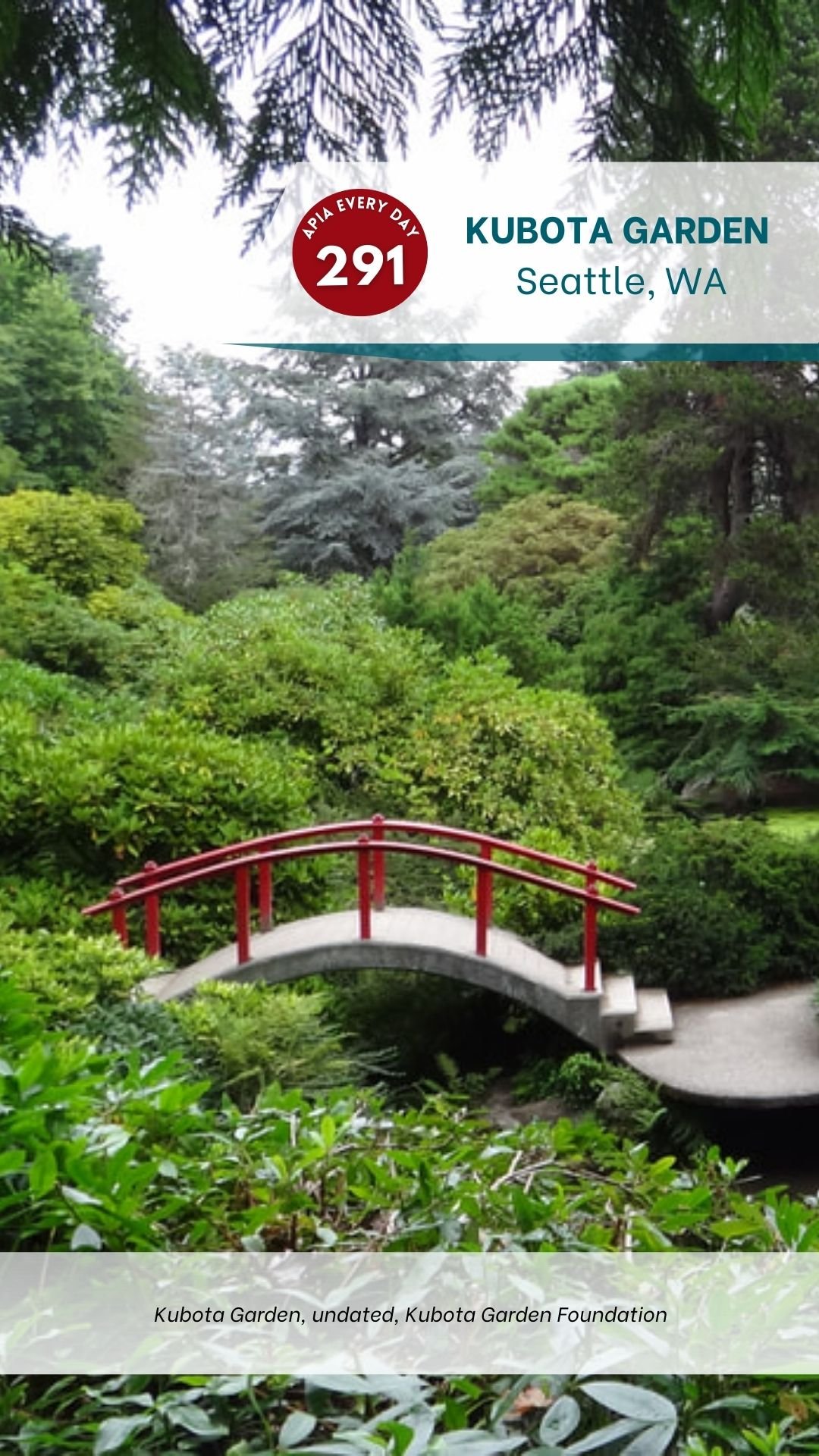

Day 291: Kubota Garden, Seattle, Washington

📌APIA Every Day (291) - The Kubota Garden in Seattle was established by first-generation Japanese immigrant Fujitaro Kubota in 1927. Representing over half a century of dedicated work by Kubota and his family, it stands as one of the earliest examples of a Japanese-style garden cultivated by an immigrant in the U.S. Rather than imitating landscapes in Japan, the design of the Kubota Garden adapts traditional Japanese aesthetics to its Pacific Northwest environment. Symbolic of the Japanese American immigrant experience, this garden has long served as an important gathering space for the Seattle community.

After immigrating to Washington State in 1906 with his family, Fujitaro Kubota worked various jobs before founding the Kubota Gardening Company in 1923. In 1927, seeking space for his business, he arranged to purchase five acres of swampland in South Seattle. Due to the Alien Land Laws at the time, which prevented Japanese immigrants from owning land, the property had to be purchased under the name of Kubota's friend, a Japanese American citizen. Kubota began cultivating his display garden, and after the Kubota family moved onto the property in 1940, he expanded his total land to 20 acres. Although it wasn’t public property, the garden became an important gathering space for the local Japanese American community.

In 1942, Executive Order 9066 forced Kubota and his family into the Minidoka incarceration camp in Idaho. While there, he tended the camp's grounds, planting trees and gardens to provide shade. Throughout the war years, the family’s Seattle house was rented out and maintained, but the garden fell into a period of severe neglect. When the Kubotas returned to the city in 1945, it took four years of labor before the garden was fully restored. During this time, Kubota also revived his gardening business and the family continued to enhance their personal garden with new features well into the 1970s. After Washington's repeal of the Alien Land Laws in 1966, Fujitaro Kubota finally gained legal ownership of his gardens. In 1973, the year of his death, Japan awarded him The Fifth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure for fostering greater appreciation of Japanese gardens and culture in Seattle.

The garden received designation as a Seattle Landmark in 1981 but soon faced redevelopment pressure from housing authorities. Following advocacy from the Japanese American community and other Seattle residents, the city purchased the property from the Kubota family. In 1987, the Kubota Garden reopened as a public park, jointly maintained by Seattle Parks and Recreation and the Kubota Garden Foundation. Today, it remains a beloved community site that preserves the legacy of early Japanese American immigrants and honors Fujitaro Kubota's enduring lifelong vision for a public Japanese garden in Seattle.

After immigrating to Washington State in 1906 with his family, Fujitaro Kubota worked various jobs before founding the Kubota Gardening Company in 1923. In 1927, seeking space for his business, he arranged to purchase five acres of swampland in South Seattle. Due to the Alien Land Laws at the time, which prevented Japanese immigrants from owning land, the property had to be purchased under the name of Kubota's friend, a Japanese American citizen. Kubota began cultivating his display garden, and after the Kubota family moved onto the property in 1940, he expanded his total land to 20 acres. Although it wasn’t public property, the garden became an important gathering space for the local Japanese American community.

In 1942, Executive Order 9066 forced Kubota and his family into the Minidoka incarceration camp in Idaho. While there, he tended the camp's grounds, planting trees and gardens to provide shade. Throughout the war years, the family’s Seattle house was rented out and maintained, but the garden fell into a period of severe neglect. When the Kubotas returned to the city in 1945, it took four years of labor before the garden was fully restored. During this time, Kubota also revived his gardening business and the family continued to enhance their personal garden with new features well into the 1970s. After Washington's repeal of the Alien Land Laws in 1966, Fujitaro Kubota finally gained legal ownership of his gardens. In 1973, the year of his death, Japan awarded him The Fifth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure for fostering greater appreciation of Japanese gardens and culture in Seattle.

The garden received designation as a Seattle Landmark in 1981 but soon faced redevelopment pressure from housing authorities. Following advocacy from the Japanese American community and other Seattle residents, the city purchased the property from the Kubota family. In 1987, the Kubota Garden reopened as a public park, jointly maintained by Seattle Parks and Recreation and the Kubota Garden Foundation. Today, it remains a beloved community site that preserves the legacy of early Japanese American immigrants and honors Fujitaro Kubota's enduring lifelong vision for a public Japanese garden in Seattle.