APIA Every Day is our commitment to learning and sharing about historic places significant to Asian & Pacific Islander Americans, every day.

Follow Us →

Day 203: Alaska Packers Association's (APA) Diamond NN Cannery, South Naknek, Alaska

📌APIA Every Day (203) - The Alaska Packers Association (APA) Diamond NN Cannery, located at the mouth of the Naknek River in Alaska, was a key site for salmon processing from 1890 until its closure in 2015. Originally a saltery, it was converted into a cannery by the APA, becoming a major industrial facility with structures dedicated to specific functions such as canning, storage, machine repairs, and housing. The cannery's workforce and accommodations were organized along ethnic lines, with bunkhouses designated for Italian, Scandinavian, Filipino, and Chinese workers, though these designations shifted over time. The cannery's operations were integral to the local community, offering employment and services, including a hospital that was used extensively during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

The cannery's early workforce consisted largely of Chinese laborers who carried out most of the canning process. However, after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted immigration, the industry turned to other ethnic groups, including Puerto Ricans, Koreans, Japanese, and Mexicans. The introduction of the Smith Butchering Machine in 1905, which could process fish more efficiently, reduced the need for manual labor and accelerated production. By the mid-20th century, Filipino workers became the primary labor force, playing a crucial role in the cannery's operations until women and college students began joining the workforce in the 1980s.

In 2015, as the cannery was set to close, the NN Cannery History Project was initiated to document and preserve its history. Led by historian Katherine Ringsmuth, the project collaborated with various historical and cultural organizations to collect stories and nominate the site for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The cannery was listed in 2021, acknowledging its historical role in Alaska's fishing industry. An exhibit titled "Mug Up" opened in 2022 at the Alaska State Museum to highlight the cannery's work culture and its diverse workforce.

Day 202: On Leong Tong House, Omaha, Nebraska

📌APIA Every Day (202) - The On Leong Tong House in Omaha, Nebraska, is a significant landmark in Chinese American immigrant history from the early to mid-20th century. Established around 1916, the On Leong Tong was a Chinese American merchants' association. It aided newly arrived immigrants by assisting with employment and providing short-term financial support. From 1938 to 1959, the building at 1518 Cass Street served as the organization's headquarters and became a focal point for Omaha's Chinese American community.

The structure, originally built as a commercial laundry in 1911, was repurposed in 1938 to house the On Leong Tong. For over two decades, it functioned as the business, social, and cultural center of Omaha's Chinese American community. The building visibly represented the Chinese American presence in the city. It displayed the Nationalist Chinese flag beneath the U.S. flag and featured a sign with Chinese characters along its cornice. The house hosted various events including Chinese holiday celebrations, multi-day feasts, business meetings, and social gatherings. It also accommodated meetings of the Gee How Oak Tin Association, an unrelated Chinese family association, further emphasizing its community importance.

The On Leong Tong House's significance extended beyond its role as a community center. It contributed to the history of Chinese immigration, community development, and cultural preservation in Omaha. The building's influence reached its peak during World War II and the early Cold War period, reflecting the changing experiences of Chinese Americans during these times.

The house's period of historical significance concluded in 1959 with the death of Chin Ming Yuet (also known as George Hay), the organization's leader, which led to the tong's dissolution. Although currently vacant, the On Leong Tong House remains the last known building associated with this organization. It stands as a tangible reminder of Omaha's early Chinatown and the impact of Chinese American merchants on the city's cultural landscape. In recognition of its historical importance, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

Day 201: Filipino American Community Hall, Bainbridge Island, Washington

📌APIA Every Day (201) - Located on Bainbridge Island, Washington, is the Filipino American Community Hall, established in 1943 and originating from the 1928 Bainbridge Island Fair Hall. In 1935, the Filipino Growers Association acquired the 10-acre property, including the hall built with lumber from the Port Blakely Mill. During World War II, Filipino farm workers managed farms after Japanese American residents were forcibly removed. In 1945, Filipino farmers incorporated as the Bainbridge Island Filipino Farmers' Association, later transferring the hall to the Filipino American Community of Bainbridge Island and Vicinity.

As the hall became a center for Filipino culture, it also took on special importance for a unique community that emerged on the island. The Filipino American Community Hall holds particular significance for the Indipino community, a group that emerged from marriages between Filipino immigrant workers and Indigenous women from various tribes who came to work on the island's farms in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The children of these unions faced challenges of identity and acceptance in pre- and post-World War II society, making the hall an essential gathering place that fostered cultural connections and provided much-needed support.

As a focal point for cultural preservation, the hall became a safe haven where Indipino individuals could explore and celebrate their dual heritage. It offered a space where they could connect with their Filipino roots through traditional cuisine, music, and dance, while also acknowledging their Indigenous ancestry. This cultural blend was particularly important for a community that often struggled to find its place in the broader social landscape of the time.

Despite challenges, including the U.S. government acquiring part of the property in the 1960s for an Army Nike site (later converted to Strawberry Hill Park), the hall continued to serve as an important cultural landmark. Its historical significance was recognized in 1995 when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, the Filipino American Community Hall continues to play a vital role in preserving and sharing Filipino and Indipino culture. On September 14th, 2024, attendees of the National APIAHiP Forum visited the hall, where they met Gina Corpuz, the hall's Project Administrator and Executive Producer of "Honor Thy Mother." Corpuz, an Indipino native of Bainbridge Island, shared the hall's history and significance. Visitors also viewed a traveling exhibit featuring posters explaining the history of Filipino migration to the U.S. and experiences on Bainbridge Island.

Day 200: Managaha Island Historic District, Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

📌APIA Every Day (200) - The Managaha Historic District, a small islet off the west coast of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, is significant for its association with Agruhubw, the Carolinian chief who led the first group of Carolinian settlers to Saipan in 1818. These settlers, displaced by storms, established the first permanent population on Saipan since the Spanish depopulated the island in the early 18th century. The district holds cultural significance for the Saipanese Carolinian community, as it contains Agrub's burial site and a commemorative statue as well as various plants and herbs used in traditional Carolinian medicine. Additionally, the district features remnants of Japanese fortifications from World War II, providing a glimpse into Japan's defensive efforts on Saipan.

Managaha Island is ecologically and historically significant, hosting colony of breeding Wedge-tailed Shearwaters, which nest in burrows mainly on the island's east side. Despite having no permanent residents, the island attracts numerous visitors due to its natural beauty and historical significance. Surrounding the island is a beach that encircles a forested area with various facilities. In recognition of its cultural and historical importance, the entire island is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.

Day 199: Isleton Chinese and Japanese Commercial Districts, Sacramento, California

📌APIA Every Day (199) - The Chinese and Japanese commercial districts in Isleton, California, emerged in the late 19th century following the town's founding by Dr. Josiah Poole in 1874. Isleton's Chinatown was established in 1878 on rented land, initially serving Chinese laborers working on levee construction and land reclamation in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. By the 1890s, it had grown into a well-established community. Japanese immigrants began arriving around the turn of the century, partly replacing the declining Chinese workforce and responding to the booming asparagus industry.

Two major fires in 1915 and 1926 reshaped the area, leading to a clear division between the Chinese area (west of F Street) and the Japanese area (east of F Street). From 1926 until World War II, Isleton's Asian American district thrived, known for its gambling halls and family-oriented community with schools teaching Chinese and Japanese languages and customs. Isleton's Chinese population began to decline in the 1930s and 1940s as younger generations moved to larger urban areas. Filipino workers began moving into the districts, while the success of the canneries maintained stable populations.

The outbreak of World War II and the subsequent incarceration of Japanese Americans in 1942 marked a turning point. During the war, Filipino and Mexican laborers occupied the Japanese district. Few Japanese Americans returned after the war, and those who did soon left for nearby cities. Today, the districts retain much of their 1920s and 1930s character, with unique architectural styles and small gardens throughout. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991, the area is currently undergoing construction for the Asian American Heritage Park, which will contribute to historic preservation, promote tourism, and tell the story of Chinese and Japanese immigrant communities in Isleton and the Delta region.

Day 198: Honouliuli National Historic Site, Oahu, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (198) - Honouliuli, opened on March 1, 1943, was the largest and longest-operating World War II incarceration and prisoner of war (POW) camp in Hawaii. Built on 160 acres in west Oahu, the camp was hidden in a deep gulch that incarcerees called jigoku dani, or "hell valley." This site became a focal point of wartime policies following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The camp held approximately 320 civilian incarcerees, mostly second-generation Japanese Americans, as well as Japanese, German, and Italian permanent residents living in Hawaii. It was divided into sections separated by barbed wire to segregate incarcerees by gender, nationality, and military or civilian status. Honouliuli was also the largest POW camp in Hawaii, incarcerating nearly 4,000 individuals, including Okinawans, Koreans, and Taiwanese captured during Pacific campaigns. In total, over 2,300 Japanese American men and women from Hawaii were incarcerated during World War II, including many prominent community leaders, teachers, journalists, religious leaders, local politicians, and World War I veterans.

Preservation efforts for Honouliuli gained momentum in 2009 when Senators Daniel K. Inouye and Daniel K. Akaka, along with then-Congresswoman Mazie Hirono, introduced bills to evaluate the site for potential inclusion in the National Park System. The site was rediscovered in 2002 by volunteers from the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii, having been largely forgotten as vegetation reclaimed the area. On February 24, 2015, President Obama designated Honouliuli as a National Monument, which was later redesignated as a National Historic Site on March 12, 2019, through the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act. This designation serves to preserve the site's history and provide educational opportunities. The site now stands as a powerful reminder of civil rights violations during wartime, aiming to educate future generations about this dark chapter in American history. Various organizations, including the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii, National Park Service, Historic Hawaii Foundation, and the University of Hawaii - West Oahu, continue to play crucial roles in preservation efforts and public education about the site's significance.

Day 197: Sikh Temple, Oak Creek, Wisconsin

📌APIA Every Day (197) - The Sikh Temple of Wisconsin was formally established in October 1999, but its roots trace back to 1997 when a small group of Sikh families began gathering in rental community halls in Milwaukee's south side. The initial location at 441 E Lincoln Ave, Milwaukee, served a growing congregation of 450-500 people. However, as the community expanded, the need for a larger space became apparent.

To accommodate this growth, the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin purchased 13 acres of land at 7512 S Howell Ave near the airport in Oak Creek. Construction of a new 17,500 square foot Gurdwara was completed on April 13, 2007. This new facility featured a library, educational areas for children, a play area, ample parking, and space for childcare. It also provided accommodations for visiting ragi jathas (priests) from around the country and the world.

Tragically, on August 5, 2012, this temple became the site of a mass shooting carried out by a white supremacist. Six people were fatally injured, and several others were wounded, drawing national and international attention discussions about hate crimes and religious tolerance. Despite this tragedy, the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin continues to serve its community, offering religious services, language instruction, and collaborating with cultural organizations to preserve and celebrate Sikh heritage. It begs the question of how we can preserve religious institutions when horrific or significant events have occurred there?

Day 196: Betsuin Buddhist Temple, Fresno, California

📌APIA Every Day (196) - Situated in Fresno, California once resided the historic Fresno Betsuin Buddhist Temple which dates back to 1899 when the first "Howakai" or religious gathering was held. In January 1900, it was officially recognized by the San Francisco headquarters as the Fresno Hompa Hongwanji. The first official service was held on January 27, 1901, led by Rev. Fukyo Asaeda from Kyoto, Japan. A three-story wooden temple was built and dedicated on April 8, 1902, by first-generation Japanese immigrants.

As the community grew, so did its challenges. In 1919, a fire destroyed the original wooden building, but the community quickly rallied to raise funds for a new structure. A concrete temple was built and dedicated in November 1920 by Rev. Kakuryo Nishijima. On November 4, 1936, the Fresno Buddhist Church was elevated to "Betsuin" status by the mother temple Hompa Hongwanji of Kyoto, Japan, indicating its direct branch status and conferring the title of "Rimban" to the head minister.

Over the years, the temple has undergone several changes and expansions. In 2010, a Family Dharma Center was dedicated at the current location on 2690 E. Alluvial Avenue in Fresno, while the original Kern Street property was sold in 2018, becoming the Burmese Mrauk Oo Dhamma Center. Construction of a new Hondo (main temple), which began in November 2020, was completed in April 2022. Today, the Fresno Betsuin Buddhist Temple serves a membership of over 1,400 people across the San Joaquin Valley. It continues to preserve its rich traditions while ensuring that the teachings of the Buddha remain relevant in modern life.

Day 195: Little Manila, Queens, New York

📌APIA Every Day (195) - Little Manila in Woodside, Queens, began forming in the 1970s when Filipino immigrants, many recruited by Elmhurst Hospital due to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, settled in the area. New York hospitals faced nursing shortages and recruited from the Philippines, bringing many Filipino nurses and their families to Queens. Those who worked at Elmhurst Hospital settled in the surrounding neighborhoods, including Woodside, where the Filipino community has since thrived. By the 1990s, 72% of Philippine immigrants in New York were registered nurses. The nearby Catholic church, St. Sebastian’s, also supported their integration, and over time, the neighborhood developed a distinct Filipino presence with numerous Filipino-owned businesses and cultural establishments.

The official recognition of Little Manila came with the co-naming of the intersection of Roosevelt Avenue and 70th Street as "Little Manila Avenue." This recognition followed a two-year advocacy effort that was triggered by a mural honoring Filipino healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A community petition led to the city council passing a bill for the co-naming in December 2021.

Currently, Little Manila is known for its Filipino businesses, including Phil-Am Food Mart and various restaurants. The area is home to approximately 85,000 Filipinos in New York City, making them the third-largest Asian group in the city. In such a diverse state, it is important to recognize and preserve the contributions of ethnic neighborhoods like Little Manila through place-based historic 📌APIA Every Day (195) - Little Manila in Woodside, Queens, began forming in the 1970s when Filipino immigrants, many recruited by Elmhurst Hospital due to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, settled in the area. New York hospitals faced nursing shortages and recruited from the Philippines, bringing many Filipino nurses and their families to Queens. Those who worked at Elmhurst Hospital settled in the surrounding neighborhoods, including Woodside, where the Filipino community has since thrived. By the 1990s, 72% of Philippine immigrants in New York were registered nurses. The nearby Catholic church, St. Sebastian’s, also supported their integration, and over time, the neighborhood developed a distinct Filipino presence with numerous Filipino-owned businesses and cultural establishments.

The official recognition of Little Manila came with the co-naming of the intersection of Roosevelt Avenue and 70th Street as "Little Manila Avenue." This recognition followed a two-year advocacy effort that was triggered by a mural honoring Filipino healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A community petition led to the city council passing a bill for the co-naming in December 2021.

Currently, Little Manila is known for its Filipino businesses, including Phil-Am Food Mart and various restaurants. The area is home to approximately 85,000 Filipinos in New York City, making them the third-largest Asian group in the city. In such a diverse state, it is important to recognize and preserve the contributions of ethnic neighborhoods like Little Manila through place-based historic preservation practices.

Day 194: Tui Manu'a Graves Monument, Manu’a, American Samoa

📌APIA Every Day (194) - The Tui Manu'a Graves Monument is a historical site on Ta'u Island, the largest island of the Manu'a group in American Samoa. Located northwest of the junction of Ta'u Village and Ta'u Island Roads on the island's west side, the monument features a stone platform about 3 feet high. The graves of several Tui Manu'a (kings of Manu'a) are marked here, including Tui Manu'a Matelita and Tui Manu'a Elisala. The graves are distinguished by sections of smoothed stones and a marble column, with a possible unmarked grave in the projection.

The formation of the Tui Manu’a title is rooted in ancient Samoan tradition, believed to be descended from the supreme god Tagaloa. The Manu’a Islands were considered sacred, and the chant "Tui Manu’a Lou Ali’i E" honored the Tui Manu’a title. The cultural and political influence of the Tui Manu’a extended across Tonga, parts of Fiji, and other Pacific islands. The Tui Manu’a kings commanded respect and tribute from these regions, as evidenced by oral traditions, cultural practices, and archaeological findings. Known as the Manuatele or the Faleselau, the empire had a broad reach, influencing Polynesia through trade and cultural exchange. Many Polynesian languages and dialects, such as those in Tikopia, Pukapuka, Uvea, and Tuvalu, have roots in or were heavily influenced by Samoa. The Tui Manu’a kings controlled and regulated interisland trade networks from Manu’a, distributing goods like basalt adzes and obsidian across the Pacific. Despite shifts in political power within Samoa, the Tui Manu’a title maintained its cultural significance. The decline of the Tui Manu’a empire led to increased autonomy for various islands, paving the way for the rise of the Tui Tonga dynasty and other regional powers.

Due to the historical significance of the Tui Manu’a title and the Tui Manu’a Graves Monument, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015. It was recognized for being a gravesite of persons of transcendent importance and conveying significant symbolic information about the culture of the islands, fulfilling Criterion A and B.

Day 193: Chinatown, Phoenix, Arizona

📌APIA Every Day (193) - Located in Phoenix, Arizona, once stood a Chinatown that developed in the 1870s as Chinese immigrants, primarily single men, formed a community to support each other amid widespread discrimination. Initially, they settled at First and Adams Street, building a community that allowed them to maintain and celebrate their Chinese heritage. By 1890, due to anti-Chinese sentiment and development pressures, the community moved several blocks south to a less visible area centered at First and Madison Streets. This new Chinatown became larger and included various businesses such as grocery stores and laundries. During this time, Louie Ong served as the unofficial mayor, maintaining order within the community.

As the Chinese community prospered, they moved out of Chinatown to take advantage of the city's growth and opportunities, distancing themselves from its negative reputation. Many Chinese-owned businesses began operating outside of Chinatown, further dispersing the Chinese population. This was further encouraged by Chinese leaders who wanted residents to relocate as a means of minimizing attention and conflict associated with high-profile Chinatowns. Additionally, urban redevelopment in the 1980s, including the construction of American West Arena, led to the demolition of the remaining Chinatown structures. Over time, the Chinese community in Phoenix integrated more fully into the broader city, contributing to its economic and social landscape. The combination of economic success, social integration, business relocation, and urban redevelopment ultimately led to the disappearance of Phoenix's Chinatown. How can we best remember and honor the contributions made in Phoenix’s Chinatown?

Day 192: Hmong Community, Walnut Grove, Minnesota

📌APIA Every Day (192) - In the early 2000s, Walnut Grove, Minnesota, experienced a dramatic demographic shift when Hmong immigrants began residing in the area. This was part of a broader movement of Hmong refugees and immigrants to Minnesota that began in the late 1970s and 1980s following the Vietnam War. Many Hmong fled Laos and Thailand due to their involvement with U.S. forces during the war, seeking stability and economic opportunities. Minnesota, particularly towns like Walnut Grove, offered welcoming conditions with available farmland, job prospects in local factories, and a slower-paced small-town environment.

Surprisingly, the decision for many Hmong families to settle in Walnut Grove was influenced by the town's depiction in the television show Little House on the Prairie. Harry Yang, a former soldier and refugee, chose Walnut Grove after his daughter suggested the town as a peaceful place to raise their family, inspired by the show's portrayal of a friendly community. By the mid-2000s, the influx of Hmong families had significantly shifted the town’s demographics, with Hmong residents comprising over a quarter of the population.

Over time, the Hmong community in Walnut Grove faced challenges as migration rates slowed and many younger Hmong moved to larger cities for educational and career opportunities. Despite the population being smaller, the community has continued to thrive as they preserve their cultural heritage while simultaneously adapting to American society. The unique experience of the Hmong community in settling in Walnut Grove highlights the importance of migration networks and cultural preservation established for a refugee group in America. It poses a question about the ways we think of place-based historic preservation practices for refugee groups settling across the U.S.

Day 191: Chinese Quarter, Jacksonville, Oregon

📌APIA Every Day (191) - Jacksonville's Chinatown, located at the intersection of Oregon and West Main Streets, was established in the early 1850s as Jacksonville developed rapidly due to the gold rush. Initially a mining camp known as Table Rock City, Jacksonville attracted various immigrants, including many Chinese seeking opportunities in the gold fields. The Chinese Quarter, which formed along West Main Street, featured a mix of wooden and later brick buildings. This neighborhood quickly became a central area for Chinese miners and residents, providing necessary services and businesses. However, as businesses moved to California Street in the 1850s and gold mining declined, the Chinese Quarter gradually fell into disuse.

In the 1870s, the Chinese community in Jacksonville had expanded, with many involved in mining and other local trades. Despite their economic contributions, the Chinese faced significant racial discrimination and restrictive legislation. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, along with other local taxes and regulations, further marginalized the community and limited their opportunities.

The decline of the Chinese Quarter was marked by a major fire on September 11, 1888, which devastated the neighborhood. Recent archaeological excavations have uncovered important artifacts from this period, providing insights into the lives of Jacksonville’s early Chinese American community. Today, the site of Chinatown is occupied by commercial buildings, residences, and Jacksonville’s Veteran’s Park. Jacksonville was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Day 190: Tongan Community, Salt Lake City, Utah*

📌APIA Every Day (190) - Salt Lake City, Utah, has a substantial Tongan population, with approximately one-quarter of all Tongans in the U.S. residing there. This makes Utah the second-largest Tongan community in the U.S., behind California and ahead of Hawai’i. As of 2010, the Tongan population in Utah was about 13,235, representing approximately one-eighth of Tonga’s total population. This is a notable concentration, with Salt Lake City having a higher Tongan population than all but the three largest cities in Tonga.

The Tongan community began forming in Utah in the 1950s when the first immigrants arrived as Mormon converts. They sought to integrate with the existing Mormon community. Over time, they were joined by additional family members and friends, attracted by educational and economic opportunities. Changes in U.S. immigration policy in the mid-1960s facilitated family reunification, leading to an increase in the Tongan population. Economic factors, such as Utah's lower cost of living compared to states like California and Hawaii, also contributed to this migration.

Currently, Utah's Tongan community faces several challenges, including economic difficulties and health issues such as high obesity rates. Religious institutions play a significant role in the community by providing support and preserving cultural practices through native language services. The community maintains its cultural identity through various events and organizations, including the annual Polynesian Day Celebration and Friend Islands Festival hosted by the National Tongan American Society. These institutions help to sustain Tongan traditions while adapting to life in Utah. How can place-based historic preservation practices be approached when considering the unique communities formed by Pacific Islander ethnic neighborhoods such as the Tongan community in Salt Lake City?

Day 189: East West Bank, Los Angeles, California

📌APIA Every Day (189) - East West Bank was established in 1973 in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, marking a significant development as the first federally chartered savings institution specifically dedicated to serving the financial needs of Chinese Americans. Founded by a group of eight individuals, the bank was created to address the barriers faced by the Chinese American community, such as language and cultural differences, which were not adequately met by mainstream banks at the time.

In its initial years, East West Bank made a substantial impact by providing bilingual services in Mandarin and Cantonese, which was crucial for many Chinese Americans who were more comfortable in these languages. This service helped overcome communication barriers and allowed community members to better navigate banking processes. The bank also played a key role in supporting Chinese American small businesses by offering loans and credit lines, helping them thrive despite the challenges of securing financing from traditional banks.

The bank’s commitment to serving the community led to significant growth in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1984, East West Bank relocated its headquarters from Chinatown to San Marino, California, to better serve the expanding Chinese American population in the surrounding suburban areas. After being acquired by the Nursalim family of Indonesia in 1991, the bank underwent several important innovations. It introduced the first trilingual ATMs in the U.S. in 1994, providing services in English, Chinese, and Spanish. Additionally, it launched bilingual online banking services in 2000, making digital banking more accessible.

In the 2000s, East West Bank continued to broaden its influence and cultural engagement. It established in-store branches in Asian American supermarkets like 99 Ranch Market, enhancing its accessibility to the community. The bank also formed partnerships with prominent cultural institutions, such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, to showcase contemporary Chinese art to American audiences. Its expansion continued internationally, including a representative office in Beijing and further growth across the U.S. and Asia. Today, East West Bank operates over 120 locations, reflecting its significant role in serving a diverse clientele and maintaining its commitment to bridging financial services between the East and West.

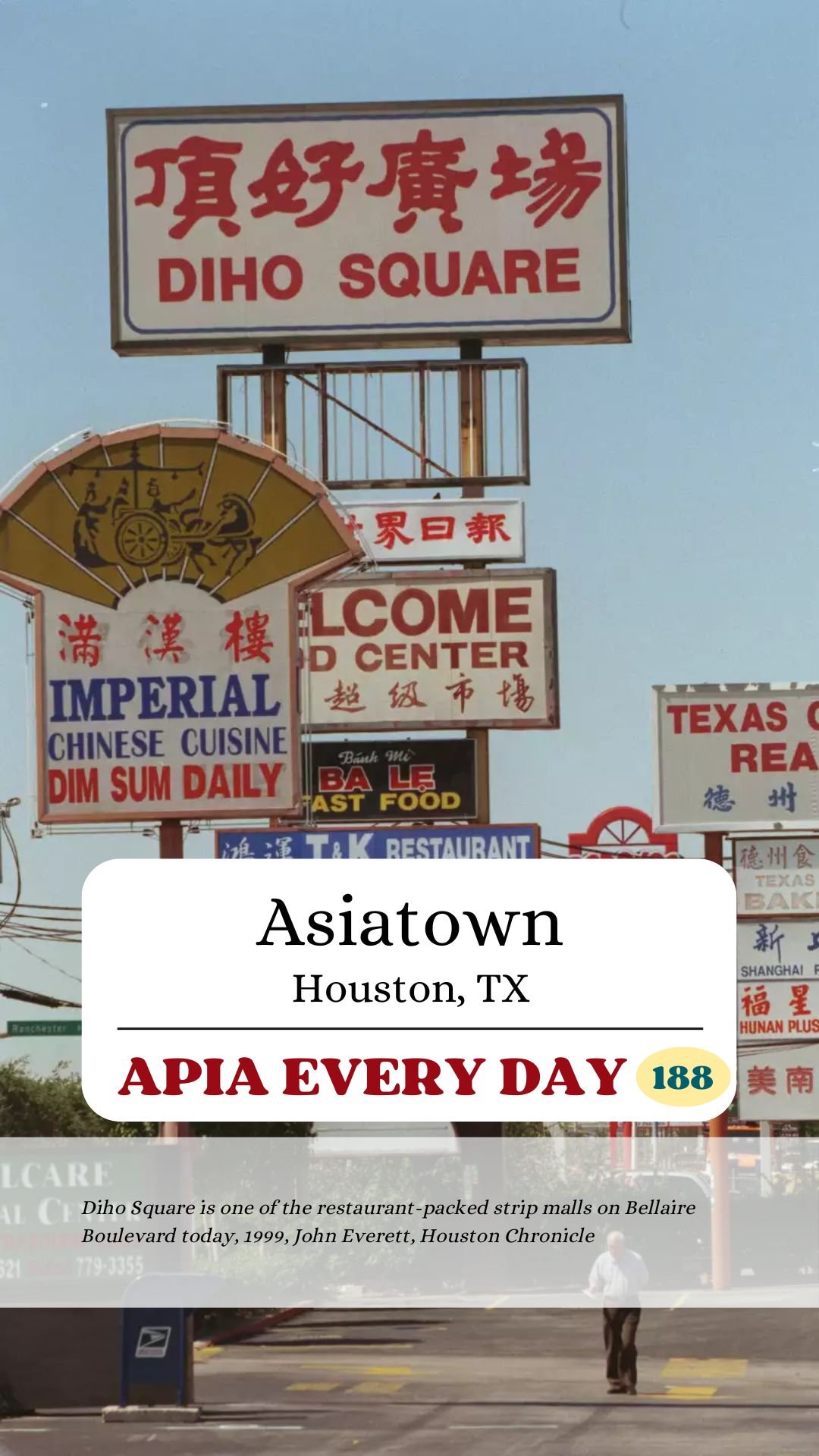

Day 188: Asiatown, Houston, Texas

📌APIA Every Day (188) - Asiatown in Houston began to develop in the early 1980s, driven by the oil bust and an increase in Asian immigration following changes in U.S. immigration laws and the fall of Saigon in 1975. Asian American businesses and residents moved from the original Chinatown in EaDo to the southwestern suburbs of Houston due to expansion limitations and high land costs in the original area. Key developments such as the opening of Diho Market in 1983 and Hong Kong City Mall were instrumental in establishing the neighborhood as a major commercial and cultural center.

In the 1960s, the construction of US 59 near Chinatown led to the demolition of 32 contiguous blocks by the Texas Eastern Corporation. Despite these disruptions, historic Chinatown remained significant through the 1970s and 1980s. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which removed restrictions on Asian immigration, and the fall of Saigon in 1975 resulted in a new wave of Asian immigrants and Southeast Asian refugees. Vietnamese refugees settled in Midtown, forming a Little Saigon that continued to thrive into the 2000s.

Today, Asiatown extends from Beltway 8 along Bellaire Boulevard and includes numerous malls, restaurants, and banks. Known as the "Wall Street of Houston" due to its concentration of financial institutions, the area reflects its diverse population. Although "Chinatown" is still commonly used, "Asia Town" is sometimes proposed to better represent the area's multicultural makeup. Organizations like the Asian/Pacific American Heritage Association work to promote unity among different ethnic groups, and cultural institutions such as the Jade Buddha Temple illustrate the district’s evolving identity.

Day 187: Little Guyana, Queens, New York

📌APIA Every Day (187) - Little Guyana, located in Richmond Hill, Queens, is home to a significant portion of New York City's Guyanese population, along with immigrants from India and Trinidad and Tobago. The neighborhood spans about 30 blocks along Liberty Avenue, the main commercial strip, which features numerous roti shops, Chinese-Guyanese restaurants, sari emporiums, bakeries, and specialty stores. Notable eateries include Singh’s Roti Shop, Sybil’s, Veggie Castle, and Little Guyana Bake Shop, serving traditional Guyanese and West Indian dishes such as roti, doubles, sweet breads, and savory pastries. Off the main strip, quieter residential streets with tidy row houses and gardens contribute to the neighborhood's distinct character.

The influx of South Asians to Little Guyana began during the 1970s and 1980s, driven by the search for better economic opportunities and political stability amid the turmoil under the Burnham/Hoyte dictatorship in Guyana. Many Guyanese immigrants, primarily of East Indian descent and often Hindu, initially settled in low-rental areas of lower and mid-Manhattan and Jamaica, Queens. Over time, the neighborhood also attracted immigrants from Trinidad, China, and India, creating a unique blend of Caribbean and South Asian cultures. The area's demographics began to shift as the Caucasian population aged and moved out, allowing Indo-Caribbean and Punjabi immigrants to establish a foothold in Richmond Hill.

Efforts to formally recognize the area culminated in the co-naming of a portion of Liberty Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard as Little Guyana Way, acknowledging the significant cultural and economic contributions of these populations in transforming Richmond Hill. By the late 1980s, the Guyanese population in Richmond Hill was estimated at around 90,000. Today, Little Guyana is known for its diverse businesses, cuisine, and cultural practices, reflecting its evolution into a melting pot of Caribbean and South Asian cultures.

Day 186: Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis, Tennessee

📌APIA Every Day (186) - Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee, was established in 1852 by fifty residents who each contributed $500 to purchase 40 acres of land. Following the Civil War, the cemetery expanded to 80 acres. In the 1870s, the original corporation was dissolved, making Elmwood one of Tennessee's oldest nonprofit cemeteries. Elmwood is the final resting place for over 75,000 people, including 266 marked and unmarked graves of Chinese Americans. An initiative led by historian Emmi Dunn Bahurlet, along with the Chinese Historical Society of Memphis and the Mid-South, is collecting information on the lives and deaths of these individuals.

The Chinese began arriving in Memphis in the mid-19th century as railroad laborers, later settling in the city and opening family grocery stores. Elmwood Cemetery started accommodating Chinese burials in the early 20th century, creating a designated section with tombstones inscribed in Chinese characters. This section marks a transition from the elaborate monument styles of the mid-19th century to simpler, more classic designs. The first Chinese individual buried at Elmwood was Sam Sam, on February 14, 1882, though his grave remains unmarked. The earliest known Chinese immigrant in Memphis was buried in 1874, likely in a pauper’s cemetery before the designated section was established. Early Chinese settlers faced numerous challenges, including diseases such as consumption, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dysentery, and tuberculosis. Several notable figures were buried at Elmwood Cemetery, with more stories emerging as the project to document their lives continues. Elmwood Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002, remains the oldest active cemetery in Memphis.

Day 185: Historic Wintersburg, Huntington Beach, California

📌APIA Every Day (185) - Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach, California, is a site of historical importance for Japanese American settlement from the late 19th century through the post-World War II period. Covering 4.5 acres, the site includes six notable structures, including the oldest Japanese mission in Southern California. The Wintersburg Japanese Mission was established in 1904 with support from Charles Furuta, a key figure in the community. Despite laws restricting land ownership for immigrants, Furuta developed a goldfish farm and later engaged in flower farming, while the mission served as a central community institution.

The mission, initially a multi-faith and multi-ethnic effort, received funding from both Japanese and European American communities. By 1930, it was recognized as the oldest Japanese church in Southern California. The mission transitioned to a formal church under the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. but remained culturally diverse. In 2014, it became a non-denominational Christian church following a formal apology from the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. for its lack of support during World War II, when Japanese American congregants were forcibly relocated.

The mission's role extended to educational and community services through Japanese Language Schools, which helped maintain cultural ties. During World War II, some mission properties were repurposed by the U.S. military, and post-war efforts focused on reclaiming and preserving the site. On February 25, 2022, a fire destroyed two of the three historic structures, leaving only the 1934 Wintersburg Japanese Church. Despite its 1986 local historic landmark designation and recognition as one of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, the site continues to face preservation challenges.

Day 184: Washington Place, O’ahu, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (184) - Washington Place, an elegant Greek-Revival house in Honolulu, Hawaii, was constructed starting in 1841 by Captain John Dominis, an American trader, and designed by Isaac Hart. Completed in 1847, it became a prominent landmark on the outskirts of Honolulu, the new capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom under King Kamehameha III. Unfortunately, Captain Dominis was lost at sea before he could reside in the house. His widow, Mary Dominis, rented out rooms to maintain the residence, including to U.S. Commissioner Anthony Ten Eyck. Inspired by its grandeur, Ten Eyck named it "Washington Place" in 1848, with King Kamehameha III's decree to retain the name indefinitely.

Architecturally, Washington Place combines Greek revival and indigenous tropical styles, reflecting early to mid-nineteenth century trends in the United States, particularly New England. The house features coral stone walls, a wood frame, two-tiered verandas, and Tuscan columns, all symmetrically arranged in a Georgian floor plan. Over the years, Washington Place has expanded significantly, now covering 17,062.50 square feet with an additional 7,000 square foot structure on its 3.1-acre grounds. These expansions have enabled the house to adapt to its residents and reflect Hawaii's evolving history.

Washington Place is most renowned as the residence of Queen Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii's last reigning monarch, who moved into the home in 1862 upon marrying John Owen Dominis, the son of John and Mary Dominis. She lived there for 55 years until her death in 1917. From 1918 to 2002, the house served as the residence for Hawaii's territorial and state governors. Today, it remains a historic home and the official residence of the Governor of Hawaii. Recognized for its historical significance, Washington Place was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007.