APIA Every Day is our commitment to learning and sharing about historic places significant to Asian & Pacific Islander Americans, every day.

Follow Us →

Day 190: Tongan Community, Salt Lake City, Utah*

📌APIA Every Day (190) - Salt Lake City, Utah, has a substantial Tongan population, with approximately one-quarter of all Tongans in the U.S. residing there. This makes Utah the second-largest Tongan community in the U.S., behind California and ahead of Hawai’i. As of 2010, the Tongan population in Utah was about 13,235, representing approximately one-eighth of Tonga’s total population. This is a notable concentration, with Salt Lake City having a higher Tongan population than all but the three largest cities in Tonga.

The Tongan community began forming in Utah in the 1950s when the first immigrants arrived as Mormon converts. They sought to integrate with the existing Mormon community. Over time, they were joined by additional family members and friends, attracted by educational and economic opportunities. Changes in U.S. immigration policy in the mid-1960s facilitated family reunification, leading to an increase in the Tongan population. Economic factors, such as Utah's lower cost of living compared to states like California and Hawaii, also contributed to this migration.

Currently, Utah's Tongan community faces several challenges, including economic difficulties and health issues such as high obesity rates. Religious institutions play a significant role in the community by providing support and preserving cultural practices through native language services. The community maintains its cultural identity through various events and organizations, including the annual Polynesian Day Celebration and Friend Islands Festival hosted by the National Tongan American Society. These institutions help to sustain Tongan traditions while adapting to life in Utah. How can place-based historic preservation practices be approached when considering the unique communities formed by Pacific Islander ethnic neighborhoods such as the Tongan community in Salt Lake City?

Day 189: East West Bank, Los Angeles, California

📌APIA Every Day (189) - East West Bank was established in 1973 in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, marking a significant development as the first federally chartered savings institution specifically dedicated to serving the financial needs of Chinese Americans. Founded by a group of eight individuals, the bank was created to address the barriers faced by the Chinese American community, such as language and cultural differences, which were not adequately met by mainstream banks at the time.

In its initial years, East West Bank made a substantial impact by providing bilingual services in Mandarin and Cantonese, which was crucial for many Chinese Americans who were more comfortable in these languages. This service helped overcome communication barriers and allowed community members to better navigate banking processes. The bank also played a key role in supporting Chinese American small businesses by offering loans and credit lines, helping them thrive despite the challenges of securing financing from traditional banks.

The bank’s commitment to serving the community led to significant growth in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1984, East West Bank relocated its headquarters from Chinatown to San Marino, California, to better serve the expanding Chinese American population in the surrounding suburban areas. After being acquired by the Nursalim family of Indonesia in 1991, the bank underwent several important innovations. It introduced the first trilingual ATMs in the U.S. in 1994, providing services in English, Chinese, and Spanish. Additionally, it launched bilingual online banking services in 2000, making digital banking more accessible.

In the 2000s, East West Bank continued to broaden its influence and cultural engagement. It established in-store branches in Asian American supermarkets like 99 Ranch Market, enhancing its accessibility to the community. The bank also formed partnerships with prominent cultural institutions, such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, to showcase contemporary Chinese art to American audiences. Its expansion continued internationally, including a representative office in Beijing and further growth across the U.S. and Asia. Today, East West Bank operates over 120 locations, reflecting its significant role in serving a diverse clientele and maintaining its commitment to bridging financial services between the East and West.

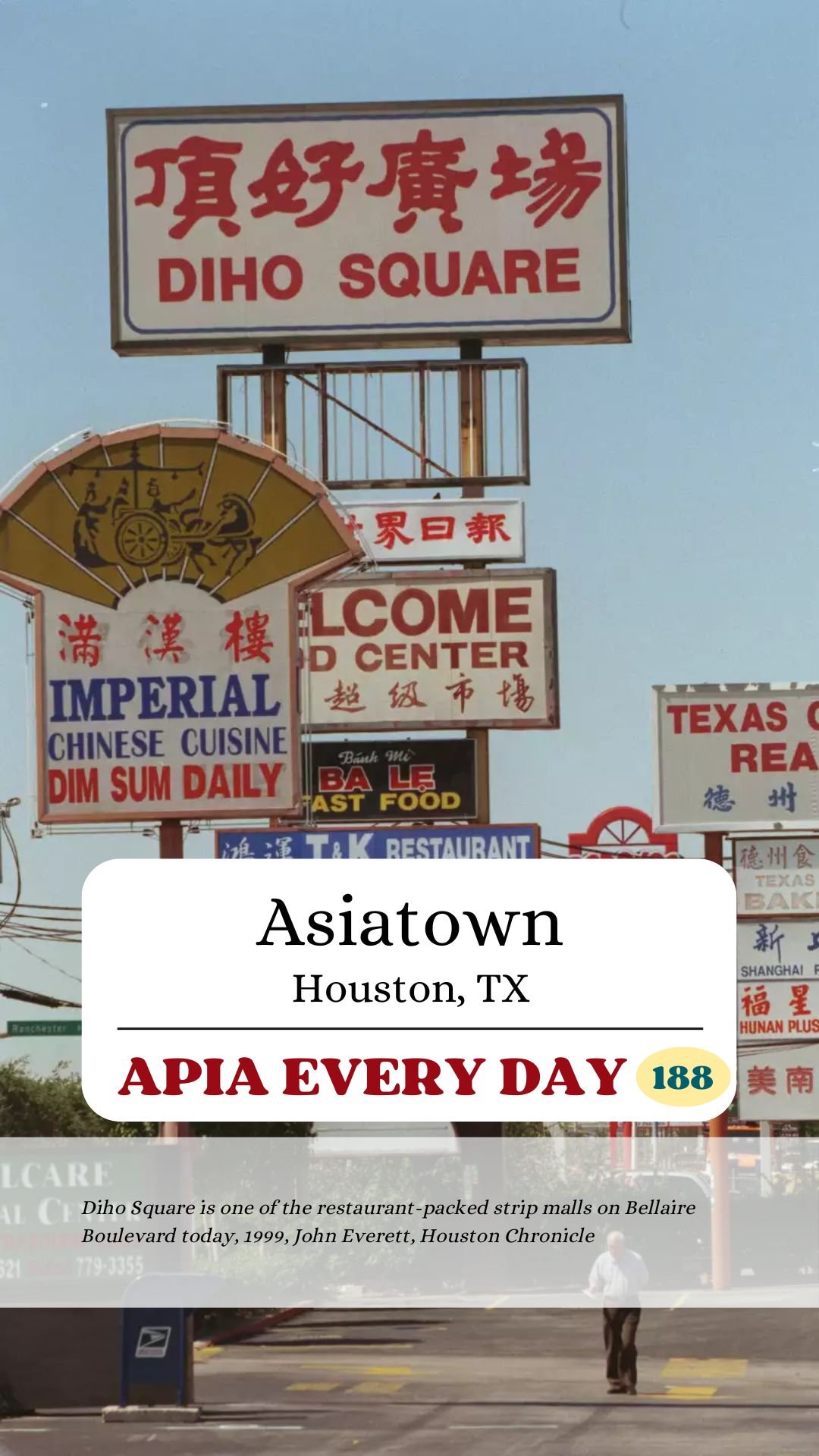

Day 188: Asiatown, Houston, Texas

📌APIA Every Day (188) - Asiatown in Houston began to develop in the early 1980s, driven by the oil bust and an increase in Asian immigration following changes in U.S. immigration laws and the fall of Saigon in 1975. Asian American businesses and residents moved from the original Chinatown in EaDo to the southwestern suburbs of Houston due to expansion limitations and high land costs in the original area. Key developments such as the opening of Diho Market in 1983 and Hong Kong City Mall were instrumental in establishing the neighborhood as a major commercial and cultural center.

In the 1960s, the construction of US 59 near Chinatown led to the demolition of 32 contiguous blocks by the Texas Eastern Corporation. Despite these disruptions, historic Chinatown remained significant through the 1970s and 1980s. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which removed restrictions on Asian immigration, and the fall of Saigon in 1975 resulted in a new wave of Asian immigrants and Southeast Asian refugees. Vietnamese refugees settled in Midtown, forming a Little Saigon that continued to thrive into the 2000s.

Today, Asiatown extends from Beltway 8 along Bellaire Boulevard and includes numerous malls, restaurants, and banks. Known as the "Wall Street of Houston" due to its concentration of financial institutions, the area reflects its diverse population. Although "Chinatown" is still commonly used, "Asia Town" is sometimes proposed to better represent the area's multicultural makeup. Organizations like the Asian/Pacific American Heritage Association work to promote unity among different ethnic groups, and cultural institutions such as the Jade Buddha Temple illustrate the district’s evolving identity.

Day 187: Little Guyana, Queens, New York

📌APIA Every Day (187) - Little Guyana, located in Richmond Hill, Queens, is home to a significant portion of New York City's Guyanese population, along with immigrants from India and Trinidad and Tobago. The neighborhood spans about 30 blocks along Liberty Avenue, the main commercial strip, which features numerous roti shops, Chinese-Guyanese restaurants, sari emporiums, bakeries, and specialty stores. Notable eateries include Singh’s Roti Shop, Sybil’s, Veggie Castle, and Little Guyana Bake Shop, serving traditional Guyanese and West Indian dishes such as roti, doubles, sweet breads, and savory pastries. Off the main strip, quieter residential streets with tidy row houses and gardens contribute to the neighborhood's distinct character.

The influx of South Asians to Little Guyana began during the 1970s and 1980s, driven by the search for better economic opportunities and political stability amid the turmoil under the Burnham/Hoyte dictatorship in Guyana. Many Guyanese immigrants, primarily of East Indian descent and often Hindu, initially settled in low-rental areas of lower and mid-Manhattan and Jamaica, Queens. Over time, the neighborhood also attracted immigrants from Trinidad, China, and India, creating a unique blend of Caribbean and South Asian cultures. The area's demographics began to shift as the Caucasian population aged and moved out, allowing Indo-Caribbean and Punjabi immigrants to establish a foothold in Richmond Hill.

Efforts to formally recognize the area culminated in the co-naming of a portion of Liberty Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard as Little Guyana Way, acknowledging the significant cultural and economic contributions of these populations in transforming Richmond Hill. By the late 1980s, the Guyanese population in Richmond Hill was estimated at around 90,000. Today, Little Guyana is known for its diverse businesses, cuisine, and cultural practices, reflecting its evolution into a melting pot of Caribbean and South Asian cultures.

Day 186: Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis, Tennessee

📌APIA Every Day (186) - Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee, was established in 1852 by fifty residents who each contributed $500 to purchase 40 acres of land. Following the Civil War, the cemetery expanded to 80 acres. In the 1870s, the original corporation was dissolved, making Elmwood one of Tennessee's oldest nonprofit cemeteries. Elmwood is the final resting place for over 75,000 people, including 266 marked and unmarked graves of Chinese Americans. An initiative led by historian Emmi Dunn Bahurlet, along with the Chinese Historical Society of Memphis and the Mid-South, is collecting information on the lives and deaths of these individuals.

The Chinese began arriving in Memphis in the mid-19th century as railroad laborers, later settling in the city and opening family grocery stores. Elmwood Cemetery started accommodating Chinese burials in the early 20th century, creating a designated section with tombstones inscribed in Chinese characters. This section marks a transition from the elaborate monument styles of the mid-19th century to simpler, more classic designs. The first Chinese individual buried at Elmwood was Sam Sam, on February 14, 1882, though his grave remains unmarked. The earliest known Chinese immigrant in Memphis was buried in 1874, likely in a pauper’s cemetery before the designated section was established. Early Chinese settlers faced numerous challenges, including diseases such as consumption, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dysentery, and tuberculosis. Several notable figures were buried at Elmwood Cemetery, with more stories emerging as the project to document their lives continues. Elmwood Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002, remains the oldest active cemetery in Memphis.

Day 185: Historic Wintersburg, Huntington Beach, California

📌APIA Every Day (185) - Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach, California, is a site of historical importance for Japanese American settlement from the late 19th century through the post-World War II period. Covering 4.5 acres, the site includes six notable structures, including the oldest Japanese mission in Southern California. The Wintersburg Japanese Mission was established in 1904 with support from Charles Furuta, a key figure in the community. Despite laws restricting land ownership for immigrants, Furuta developed a goldfish farm and later engaged in flower farming, while the mission served as a central community institution.

The mission, initially a multi-faith and multi-ethnic effort, received funding from both Japanese and European American communities. By 1930, it was recognized as the oldest Japanese church in Southern California. The mission transitioned to a formal church under the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. but remained culturally diverse. In 2014, it became a non-denominational Christian church following a formal apology from the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. for its lack of support during World War II, when Japanese American congregants were forcibly relocated.

The mission's role extended to educational and community services through Japanese Language Schools, which helped maintain cultural ties. During World War II, some mission properties were repurposed by the U.S. military, and post-war efforts focused on reclaiming and preserving the site. On February 25, 2022, a fire destroyed two of the three historic structures, leaving only the 1934 Wintersburg Japanese Church. Despite its 1986 local historic landmark designation and recognition as one of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, the site continues to face preservation challenges.

Day 184: Washington Place, O’ahu, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (184) - Washington Place, an elegant Greek-Revival house in Honolulu, Hawaii, was constructed starting in 1841 by Captain John Dominis, an American trader, and designed by Isaac Hart. Completed in 1847, it became a prominent landmark on the outskirts of Honolulu, the new capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom under King Kamehameha III. Unfortunately, Captain Dominis was lost at sea before he could reside in the house. His widow, Mary Dominis, rented out rooms to maintain the residence, including to U.S. Commissioner Anthony Ten Eyck. Inspired by its grandeur, Ten Eyck named it "Washington Place" in 1848, with King Kamehameha III's decree to retain the name indefinitely.

Architecturally, Washington Place combines Greek revival and indigenous tropical styles, reflecting early to mid-nineteenth century trends in the United States, particularly New England. The house features coral stone walls, a wood frame, two-tiered verandas, and Tuscan columns, all symmetrically arranged in a Georgian floor plan. Over the years, Washington Place has expanded significantly, now covering 17,062.50 square feet with an additional 7,000 square foot structure on its 3.1-acre grounds. These expansions have enabled the house to adapt to its residents and reflect Hawaii's evolving history.

Washington Place is most renowned as the residence of Queen Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii's last reigning monarch, who moved into the home in 1862 upon marrying John Owen Dominis, the son of John and Mary Dominis. She lived there for 55 years until her death in 1917. From 1918 to 2002, the house served as the residence for Hawaii's territorial and state governors. Today, it remains a historic home and the official residence of the Governor of Hawaii. Recognized for its historical significance, Washington Place was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007.

Day 183: Riverside Chinatown, California

📌APIA Every Day (183) - Located in Riverside, California were two Chinatowns, both now gone but well-documented through local interest and archaeological work. The first Chinatown was established in the downtown area on Ninth Street, including laundries, small restaurants, and other businesses. After a fire destroyed it, a second Chinatown was established in 1885 in the Tequesquite Arroyo near Mt. Rubidoux. Known as "Little Gom-Benn," this community had up to 400 residents, many from the Gom-Benn village in the Toishan region of southern China.

Wong Nim, Wong Gee, and Gin Duey leased 7 acres of land outside Riverside's Mile Square in 1885 and became full owners of Riverside's second Chinatown by 1888. Despite a coal stove explosion destroying the community in 1893, they rebuilt the area, which thrived until the 1920s. During peak seasons, up to 3,000 Chinese laborers lived in or near the groves, picking and packing fruit. By the 1930s, however, the community declined due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and decreasing Chinese population. George Wong, an early resident, became the last caretaker of Chinatown until his death in 1974.

In 1968, Riverside Chinatown was designated as a historic resource and later listed as a State Point of Historical Interest and a City landmark. Following George Wong's death, the site was purchased by the Riverside County Superintendent of Schools, leading to archaeological testing by the Great Basin Foundation in 1984, which unearthed significant artifacts and preserved most of the site for future study. Despite a development threat in 2008, the Save Our Chinatown Committee successfully overturned the city's approval for a medical office building in 2012, ensuring the preservation of Riverside Chinatown's historical legacy.

Today, the site of Riverside's second Chinatown is marked but closed to the public, surrounded by a chain-link fence with a historical marker at the corner of Tequesquite and Palm Avenues. The Chinese Pavilion in downtown Riverside serves as a memorial to the former Chinese community. Many descendants of Riverside's Chinese residents have resettled in other parts of Southern California and formed the Gom-Benn Village Society, which continues to hold annual meetings in Los Angeles. The Riverside Chinatown archaeological site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

Day 182: Asan Beach Unit, War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam

📌APIA Every Day (182) - The Asan Beach Unit, one of the seven units in the War in the Pacific National Park, has a varied historical background. Originally, the site hosted a leper colony from 1892 until a typhoon destroyed it in 1900. In 1901, the area was converted into a prison camp for Filipino insurrectionists. During World War I in 1917, it became a detention site for German sailors from the SMS Cormoran. By 1922, the site had been repurposed as a U.S. Marine Corps camp, featuring a quartermaster depot, small arms range, and barracks.

During World War II, Asan Beach's strategic importance increased significantly. In 1941, Japanese forces began reconnaissance missions over Guam and bombed the island in early December, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. This led to the Japanese occupation of Guam. The local CHamoru population was subjected to forced labor, including the construction of defensive structures and cultivation of food for Japanese troops. The U.S. began an extensive bombardment of Asan and Agat beaches on June 16, 1944, in preparation for a planned invasion. Despite delays due to other engagements, the invasion was rescheduled for July 21, 1944.

On July 21, 1944, U.S. Marines landed on Asan Beach under heavy Japanese defense. The Marines managed to secure the area by July 28, though fighting continued until August 10. Following World War II, the area served various purposes, including as a Navy Seabees headquarters and a Vietnamese refugee camp. It is now part of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, which preserves historical resources and memorials related to the Battle of Guam, such as the Liberator's Memoria. The retaking of Guam is commemorated annually on July 21st, known as “Liberation Day.”

Day 181: Grace Nicholson Building, USC Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, California

📌APIA Every Day (181) - The USC Pacific Asia Museum, located in Pasadena, is housed in the historic Grace Nicholson Building, a Chinese-style mansion completed in 1924. Grace Nicholson, born in Philadelphia in 1877, moved to California in 1901 and established a curio shop in Pasadena, initially focusing on Southwestern Native American art. Her expertise and growing interest in Asian art led her to commission the construction of the building, designed by the architectural firm Marston, Van Pelt, and Maybury, inspired by the Imperial Palace Courtyard style of Beijing. The building, featuring authentic Chinese materials and craftsmanship, opened in 1925, becoming a cultural hub with galleries, an auditorium, and Nicholson's private apartment.

Grace Nicholson donated the building to the City of Pasadena in 1943, retaining her private quarters until her death in 1948. The Pasadena Art Institute, later renamed the Pasadena Art Museum, occupied the building until 1970. In 1971, the Pacificulture Foundation moved in, and in 1987, the foundation purchased the building, transforming it into the Pacific Asia Museum. In 2013, the museum partnered with the University of Southern California, becoming the USC Pacific Asia Museum. The building is celebrated for its historical and architectural significance, with a courtyard inspired by traditional Chinese gardens and symbolic elements like Taihu rocks, dragons, and koi ponds. The Grace Nicholson Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and has been designated as a Cultural Heritage Landmark by Pasadena and Los Angeles, as well as a Historical Landmark by the State of California.

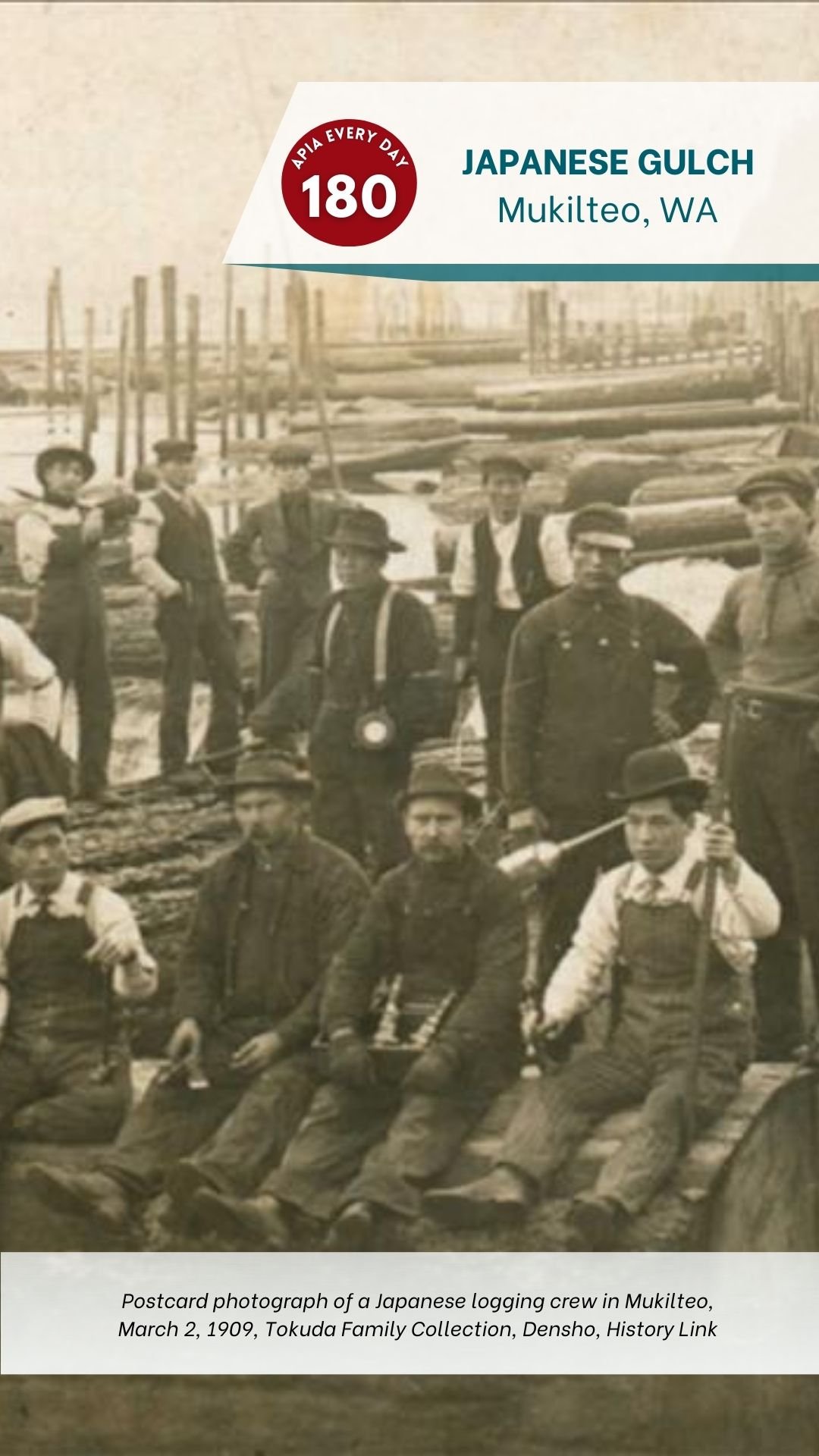

Day 180: Japanese Gulch, Mukilteo, Washington

📌APIA Every Day (180) - The Japanese Gulch, a segregated area for Japanese immigrants in Mukilteo, Washington, was formed in the early 1900s. During this time, the town hosted a significant population of Japanese immigrants, primarily due to the Crown Lumber Company’s recruitment efforts. They worked at the lumber mill and resided in company-owned housing near the mill site. Despite the segregation, they engaged in efforts to assimilate by attending church, learning English, and sending their children to local schools, while also retaining aspects of their Japanese heritage.

Japanese immigrants initially came to the Puget Sound region in the 1890s, seeking better economic opportunities amid social and economic upheaval in Japan. They found work in industries such as railroad construction, logging, and fishing. In Mukilteo, Japanese laborers were crucial to the Crown Lumber Company's operations. The company, facing a shortage of white laborers, recruited Japanese workers who earned a reputation for their hard work and reliability. This created a relatively peaceful coexistence in Mukilteo, unlike other areas where Japanese workers faced significant hostility and violence. While they participated in local activities and integrated into the broader society, they still faced economic limitations and social challenges.

The Crown Lumber Company’s closure in 1930 led to the dispersal of the Japanese community as residents moved in search of new opportunities. The area reverted to its natural state, with few physical traces of the once-thriving community remaining. The social history of Mukilteo, Washington, has made Japanese Gulch eligible for National Historic Landmark status under Criterion 6 for Archaeology, as suggested in the AAPI National Historic Landmark Theme Study.

Day 179: China Alley, Hanford, California

📌APIA Every Day (179) - China Alley in Hanford, California, is a historic district established in the 1870s during the expansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad. As the railroad extended through the area, many Chinese laborers arrived to work on the railway and later on the farms. These immigrants primarily came from the Sam Yup region in Guangdong province, consisting of the three counties of Namhoi, Poonyu, and Shuntak. Initially, the community provided essential services and labor for the burgeoning town of Hanford, which was rapidly developing in California’s Central Valley.

The Chinese community in Hanford faced segregation and discrimination but still managed to create a vibrant and self-sufficient ethnic neighborhood known as China Alley. This area soon included a wide range of establishments, such as homes, restaurants, boarding houses, general merchandise stores, herb shops, groceries, laundries, gambling establishments, a Chinese school, and the Kwan Tai Temple, which was constructed in 1882. Over the years, China Alley became a bustling "city within a city," where residents maintained their cultural traditions and businesses. Despite the challenges posed by segregation and local ordinances, the Chinese community managed to thrive and sustain their unique cultural identity within Hanford. The population of China Alley began to decline during World War II, as many residents moved away or integrated into broader American society.

In the 1970s, the China Alley Preservation Society (CAPS) was formed to address the deteriorating condition of the Taoist Temple and other historic buildings. The society’s efforts led to the cleaning, research, and curation of the Taoist Temple Museum, which opened in 1982. In 2011, China Alley was listed on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places due to threats from disuse, deferred maintenance, water damage, and vandalism. Although a fire in 2021 heavily damaged the Taoist Temple Museum, restoration efforts are ongoing. Today, the preservation of China Alley continues to highlight the historical and cultural significance of this Chinese American experience in California.

Day 178: Rohwer Relocation Center Memorial Cemetery, Desha, Arkansas

📌APIA Every Day (178) - The Rohwer Relocation Center Memorial Cemetery, located in Desha County, Arkansas, is one of the few remaining Japanese American incarceration site cemeteries in the U.S. Established during World War II, the cemetery was built by Japanese Americans incarcerated at the Rohwer Relocation Center from 1942 to 1945 [See Day 160 Post]. It features several monuments, including those honoring Japanese American soldiers who were drafted during the war. The cemetery includes historic monuments, concrete headstones, entrance markers, and a bench, all designed and constructed by the incarcerated Japanese Americans. Additionally, 17 flowering cherry trees were planted in 1994 to replicate the original design, which included water features and bridges.

In 1945, two large concrete monuments were erected in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. The first monument, adorned with floral patterns and artwork reflective of Japanese and American cultures, was dedicated to all those who died while incarcerated at the center. The second monument commemorates the young men from Rohwer who served and died in Europe as part of the U.S. Army’s 100th Battalion and 442nd Combat Team. In 1982, a granite monument with a bronze eagle was added to honor both Japanese American incarcerees and soldiers who died during the war. The cemetery was designated a National Historic Landmark a decade later in 1992 and has been preserved and documented through grants and efforts from various organizations, ensuring its history and significance are not forgotten.

When Rohwer officially closed in 1945, its buildings were auctioned off and removed, with the land repurposed for agriculture. Most of the Japanese Americans left Arkansas, either returning to the West Coast or relocating elsewhere in the U.S. A total of 168 Japanese Americans died at Rohwer, with those who chose burial laid to rest in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. Today, only the cemetery and a deteriorating smokestack from the hospital remain of the original center, serving as a reminder of the tragic events that occurred not only at this site but also at the nearby Jerome incarceration camp.

Day 177: Old Vatia, Tutuila Island, American Samoa

📌APIA Every Day (177) - Old Vatia is one of the ancient villages on Tutuila Island in American Samoa, located on the north shore at Vatia Bay. The village is accessible by American Samoa Highway 006, which is the only road passing through the National Park of American Samoa. Nestled at the base of Pola Ridge, surrounded by lush greenery and jungle-covered peaks, Vatia is the central point in the Tutuila-section of the park and is part of Vaifanua County.

Vatia, literally translating to “between the tombs of those with paramount status,” has a rich history dating back to its original inhabitants living on a narrow ridge known as Toafaiga in the 18th century. Archaeological excavations in the 1980s uncovered remnants of various structures and house foundations, including one constructed from coral slabs that may have served as a ceremonial or communal gathering place. The remains found in Old Vatia have been dated to between 1300 AD and 1750 AD. These findings reveal well-preserved house platforms atop earthen mounds encircled by basalt boulders, offering invaluable insights into the history of Polynesian Samoans.

During World War II, several concrete bunkers were constructed in Vatia, and their remnants can still be seen around the beach area. The road between Vatia and Afono is noted for its ornamental plant and flower gardens. At the end of this road in Vatia is a school, with a trail starting beyond it that leads into the national park and ends at a rocky cliff facing Pola Island. Many residents of Vatia work at the canneries in Pago Pago, and there is public transportation available via Aiga buses that travel between Fagatogo and Vatia. Additionally, the waters near Vatia witnessed the return of Apollo 11 to Earth in 1969, with a copy of the American Samoan flag carried by the mission now displayed at the Jean P. Haydon Museum in Pago Pago. There is still much to learn about the history and events that occurred in Vatia, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.

Day 176: Loaloa Heiau, Maui, Hawai’i

Loaloa Heiau, situated in Kaupo on the Island of Maui, is the largest and best-preserved luakini heiau on the island. The heiau overlooks the rural community of Kaupo, with views of the Pacific Ocean to the south and the Manawainui Valley to the north. Historically, early Hawaiian shrines were simple structures built by families and small communities. As the population grew and religious practices evolved, larger heiau were constructed for public ceremonies. The ali'i (chiefs) worshiped four major gods—Lono, Kane, Kanaloa, and Ku—while commoners worshiped individual family gods and the major gods under the direction of high priests.

Loaloa Heiau, built around 1730 for ali'i 'ai moku Kekaulike, ruler of Maui, exemplifies a luakini heiau. The structure features a three-tiered rectangular raised platform, divided into eastern and western sections by a stone wall, with overall dimensions of 115 feet by 500 feet. The walls are terraced for stability. Heiau in ancient Hawaii varied in size and function, from single upright stones to large, complex structures. Larger heiau were typically built by the ali'i, and the most complex, the luakini heiau, could only be constructed by an ali'i 'ai moku (paramount chief). These heiau were used for rituals involving human or animal sacrifice and symbolized the paramount chief's authority over his lands and people.

In 1802, Kamehameha I, while en route to conquer Kauai, stopped at Maui and rebuilt Loaloa Heiau, dedicating it to Ku. Following Kamehameha I's unification of the Hawaiian Islands, the influence of Maui's ali'i 'ai moku and religious centers like Kaupo declined. The traditional Hawaiian religious system was further dismantled in 1819 when Kamehameha's successor, Liholiho, ended the kapu system, leading to the abandonment and ruin of many heiau, including Loaloa Heiau. This marked a significant shift in Hawaiian culture as many ancient religious sites fell into disuse. Because of its significant cultural importance, it was designated a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

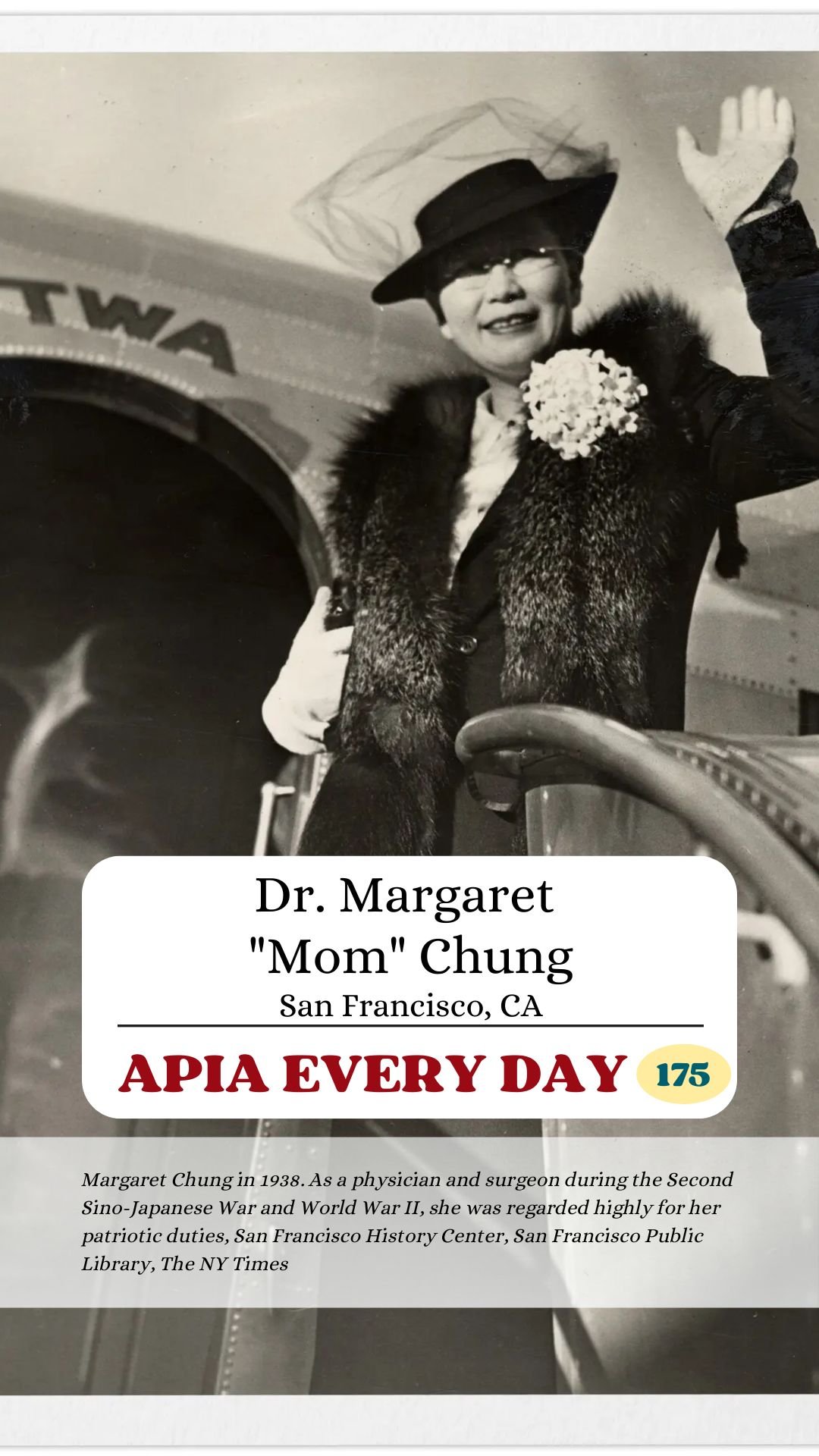

Day 175: Dr. Margaret "Mom" Chung, San Francisco, California

📌APIA Every Day (175) - Dr. Margaret “Mom” Jessie Chung was the first Chinese American woman to become a physician, opening one of the first Western hospitals in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1920s. Born in Santa Barbara, California, in 1889 to Chinese immigrant parents, she was the eldest of eleven children and helped raise her siblings. Determined to become a medical missionary, she worked her way through medical school at the University of Southern California, graduating in 1916. After being rejected by the Presbyterian missionary board because of her race, she pursued a career in medicine, first as a surgical nurse and later as a surgeon, eventually opening a private practice that served Hollywood celebrities.

In 1922, Dr. Chung moved to San Francisco and established a clinic in Chinatown to provide medical care to Chinese women. She faced skepticism and rumors due to her status as a young, single woman who wore masculine clothing. Despite these challenges, she attracted a diverse clientele, including non-Chinese patients and members of the LGBTQ+ community. During World War II, she became known for her connections with her “adopted sons,” American military soldiers, sailors, and airmen. These "sons" and their guests, including movie stars and military officials, were frequently hosted at her San Francisco home for weekly dinners. Dr. Chung used her influence to support the Allied war effort and lobbied for the creation of the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services (WAVES), the women’s branch of the naval reserves, despite facing prejudice due to her race, gender, and sexuality.

Dr. Chung passed away from cancer in 1959 at the age of 69, and her contributions to the medical field are still remembered today. A memorial to Chung is included in the Chicago Legacy Project’s Legacy Walk, honoring the accomplishments of LGBTQ people.

Day 174: Amot Taotao Tåno' Farm, Dededo, Guam

📌APIA Every Day (174) - Amot Taotao Tano Farm, located in Dededo, Guam, has been a vital part of the community since its establishment in 2010 by Bernice Tudela Nelson. The farm spans 2.5 acres and contains over 200 medicinal plants, many native to Guam and others from places like China, the Philippines, Japan, Pohnpei, Palau, and the U.S. The name 'Amot Taotao Tano' translates to "Medicine for the People of the Land" reflecting the farm's mission to protect and preserve Guam's native medicinal plants while perpetuating CHamoru traditional healing practices which is currently a dying practice.

Bernice Nelson, inspired by her suruhana (traditional healer) aunt, dedicated herself to traditional medicine and healing later in life. Her passion for herbal medicine and traditional CHamoru practices led her to open the farm, where she has been educating various groups, organizations, and families about the importance and use of these medicinal plants for over a decade. The farm also aims to teach CHamoru youths about traditional healing practices, emphasizing the spiritual aspect of medicine preparation, often incorporating prayers like "Hail Mary" during the process.

Recently, the farm's future has become uncertain due to a lease issue with the CHamoru Land Trust Commission (CLTC). Bernice applied for a small business assistance loan to help repair damages sustained from Typhoon Mawar, which brought attention to her lease. Under the Organic Act, Bernice needed to prove that her family was living on Guam before 1950 to keep the land lease. She faced challenges finding the necessary documentation due to incomplete records from that time. Eventually, she managed to gather evidence, including her grandfather's birth and baptism certificates, proving her family's residency before 1950. Despite this, the final decision lies with the CLTC board, which is expected to meet soon to determine the fate of the farm. However, there is hope that Amot Taotao Tano Farm can continue to serve its mission in preserving traditional healing practices for future generations

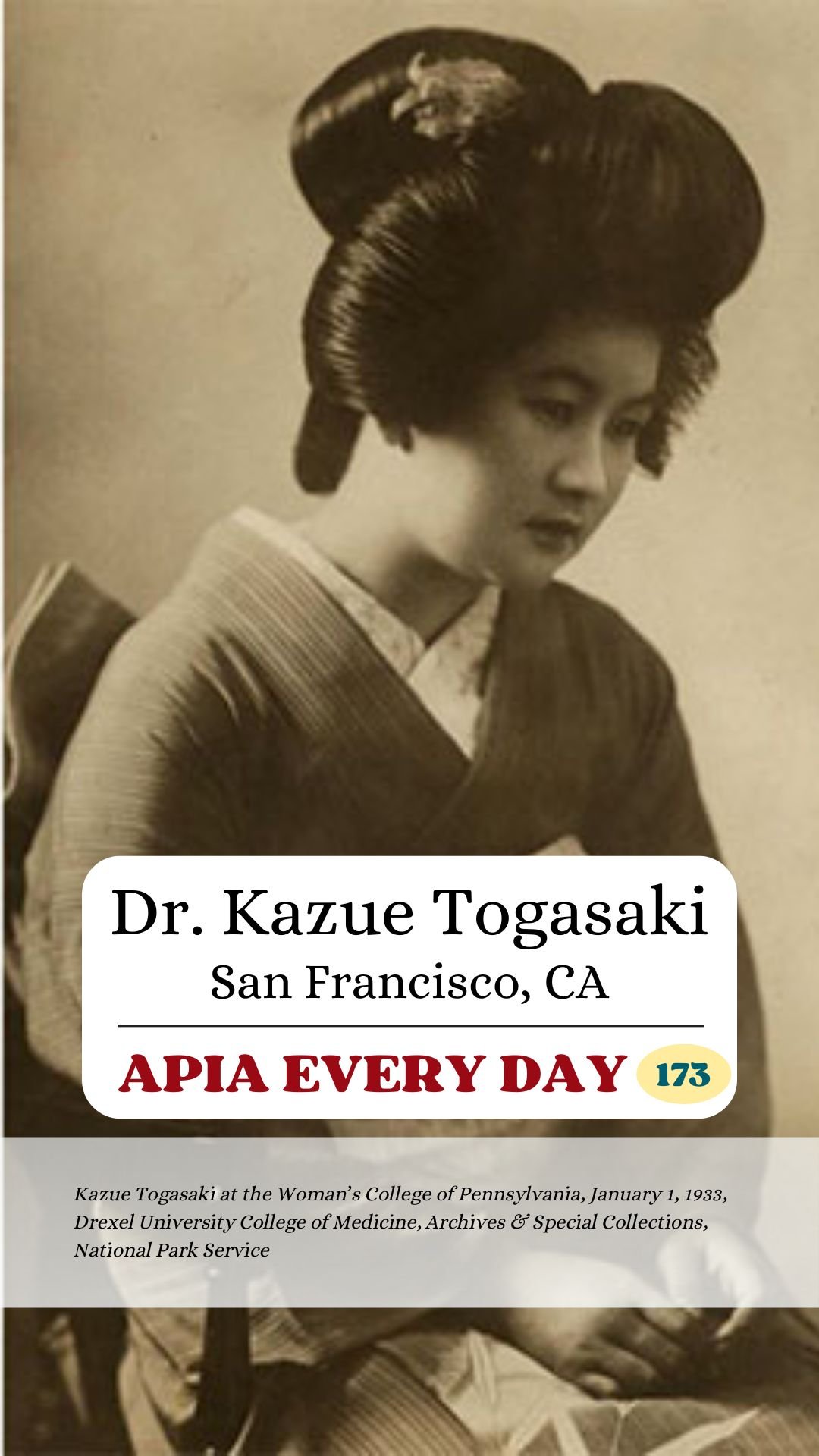

Day 173: Dr. Kazue Togasaki, San Francisco, California

📌APIA Every Day (173) - Dr. Kazue Togasaki, born in 1897 to Japanese immigrant parents in San Francisco, was one of the first two Japanese American women to earn a medical degree in the U.S. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires, she witnessed her mother convert their church into a makeshift hospital. This experience inspired Togasaki and several of her siblings to pursue careers in medicine.

Togasaki earned a degree in Zoology from Stanford University but struggled to find work in San Francisco due to racial discrimination. She faced similar treatment when she was younger, being forced to switch schools due to racial segregation. Despite excelling in a nursing program, she was not hired. Undeterred, she attended medical school at the Women’s College of Pennsylvania and graduated in 1933 [See Day 80 Post on Anandi Gopal Joshi who also graduated]. Upon returning to San Francisco, she established a medical practice and became a key healthcare provider for the Japanese American community. However, the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 led to the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans, including Togasaki, who was sent to multiple American concentration camps. There, she set up medical facilities and provided essential care, including delivering over 50 babies in her first month at the Tanforan Assembly Center.

After her release in 1943, Togasaki returned to her home in San Francisco, which had been ransacked during her forced imprisonment. She rebuilt her medical practice and continued to serve the community for over 40 years. In 1970, she was recognized as one of the "Most Distinguished Women" by the San Francisco Examiner. Dr. Kazue Togasaki passed away in 1992 at the age of 95, leaving a lasting impact on the healthcare landscape for Japanese Americans in San Francisco.

Day 172: The Queen's Medical Center, Honolulu, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (172) - The Queen’s Medical Center, originally known as the Queen’s Hospital, was founded in 1859 at Manamana in Honolulu, Hawaii. King Kamehameha IV highlighted Hawaii’s population decline due to diseases introduced by foreigners in his 1855 speech to the Hawaiian Legislature. He proposed two acts: "An Act to Institute Hospitals for the Sick Poor," aimed at establishing hospitals in Honolulu and Lahaina, and the "Act to Mitigate the Evils and Diseases Arising from Prostitution," which included measures to combat venereal diseases through registration and examination of prostitutes.

In 1859, King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma personally raised funds and contributed their own money to establish The Queen's Hospital. The initial building, made from coral blocks and California redwood, was completed at Manamana for $14,728.92. It opened in 1860, providing healthcare services during ongoing health crises, including smallpox epidemics affecting the Hawaiian population.

The hospital expanded over the years and eventually relocated to downtown Honolulu. In 1967, it was renamed The Queen's Medical Center to better represent its growth and stature as Hawaii's largest private hospital. Today, The Queen's Medical Center continues to fulfill its founders' mission, offering comprehensive healthcare services to Native Hawaiians and all residents of Hawaii. Known for its advanced medical facilities, including the state's largest MRI, it remains a crucial part of Hawaii's healthcare system, prioritizing community health and well-being.

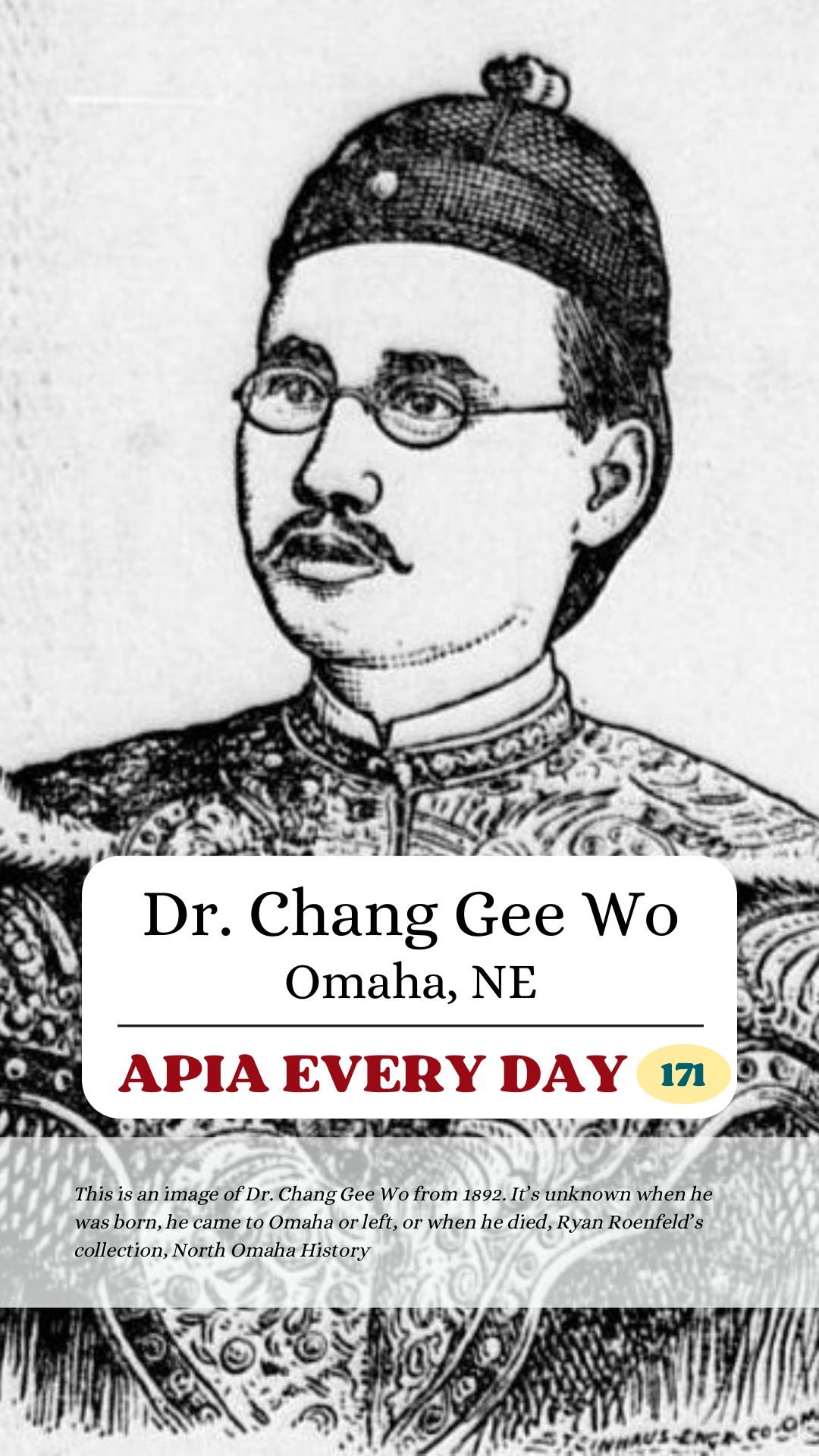

Day 171: Dr. Chang Gee Wo, Omaha, Nebraska

📌APIA Every Day (171) - In the late 19th century, Dr. Chang Gee Wo became a prominent Chinese physician in Omaha, Nebraska. His practice, located at 519 1/2 North 16th Street, offered free consultations and operated daily. Dr. Chang specialized in traditional Chinese herbal medicine, providing various patent medicines for different ailments. These included remedies like the "Last Manhood Cure," "Sick Headache Cure," and "Female Weakness Cure," each priced at $1. These medicines were prepared by the Chinese Medicine Company, which had its headquarters in Omaha and an office in Beijing.

Despite his success and popularity, Dr. Wo faced significant challenges due to racial discrimination toward Chinese immigrants and traditional Chinese medicine. Many Chinese doctors, including Dr. Wo, were often labeled as "quacks" by the American medical establishment and faced legal and social persecution. The medical community and law enforcement frequently targeted Chinese physicians, accusing them of practicing without proper licenses and seeking to undermine their businesses through regulations and sting operations.

Eventually, Dr. Wo relocated his practice to Portland, Oregon, where he continued to operate under the banner of the Chinese Medicine Company. His advertisements from the early 20th century indicate that he maintained a presence in Portland's medical market until at least 1924. Dr. Wo's career illustrates the broader challenges faced by Chinese immigrants and practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine in the United States during this period. Their contributions to healthcare were often marginalized, and they had to navigate a hostile environment that questioned their legitimacy and sought to exclude them from the medical profession.