APIA Every Day is our commitment to learning and sharing about historic places significant to Asian & Pacific Islander Americans, every day.

Follow Us →

Day 163: Bernie’s Teriyaki, Los Angles, California

📌APIA Every Day (163) - Bernie's Teriyaki, established in 1977, was a Filipino-style barbecue restaurant with influences from Hawaiian plate lunches. Located in Historic Filipinotown in Los Angeles, California, the restaurant was founded by August and Fely B. Cruz and was considered the oldest Filipino-owned establishment in the area.

The restaurant was known for its budget-friendly pricing, with most menu items priced around $5. Portions were generous, often sufficient for two meals or a substantial single serving. Bernie's Teriyaki became a local favorite for those seeking hearty, satisfying meals in a casual setting. Despite offers from developers to purchase the land, Bernie’s continued to operate, maintaining its commitment to affordable dining.

There is limited information on Bernie’s Teriyaki’s history, but it is said to have closed sometime in 2019. Although Bernie’s Teriyaki is no longer in operation, its presence highlighted the influence of the diverse Asian American population on the culinary landscape of Los Angeles.

Day 162: Bamboo Inn, Indianapolis, Indiana

📌APIA Every Day (162) - The Bamboo Inn, situated on 39 Monument Circle in Indianapolis, Indiana, was established on July 13, 1918 as a Chinese American within the Circle Theatre Building. Initially managed by George Gong, the restaurant quickly changed hands to Tuen Hip Wey, a Chinese American group from Chicago. The Bamboo Inn featured a resident orchestra, bamboo décor, and a balcony, becoming a popular spot for its evening and late-night musical entertainment. Under head chef Henry Shinohara, the menu offered a mix of Americanized Chinese dishes, traditional fare, and French cuisine, setting it apart in the Indianapolis dining scene.

The 1920s were marked by both success and controversy for the Bamboo Inn. In 1920, it faced legal issues over allegations of serving impure meat, resulting in a court case that brought negative publicity. Despite these challenges, the restaurant continued to attract patrons and emphasized its cleanliness in advertisements. It also became a target for robberies due to its late hours and opulent interior. In 1932, the Bamboo Inn expanded its entertainment offerings with the opening of Club Orientale on the second floor, which featured midnight floorshows and dancing. However, the club's operation was short-lived, ceasing activities within a few years due to the Great Depression.

During World War II, the Bamboo Inn remained active in the community, with employees raising significant funds for the war bond drive. After its lease at the Circle Theatre expired in 1946, the restaurant relocated to the English Hotel and subsequently to other locations. In the 1950s, the Bamboo Inn continued to offer live music and entertainment. By 1961, the restaurant was sold and renamed Jong Mea, ending its long-standing presence in Indianapolis. The last known owner was Henry Guy Chung, who had managed the Bamboo Inn for decades as part of the Tuen Hip Wey group. Today, the site of the original Bamboo Inn is part of the Hilbert Circle Theatre and continues to be a reminder of the tenacity and success of Chinese American business owners who endured exclusionary laws during this period.

Day 161: South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association Protests, Manhattan, New York

📌APIA Every Day (161) - Madison Square Park in Manhattan became a central location for the South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association’s (SALGA) protests after the Federation of Indian Associations (FIA) banned them from the India Day Parade. Originally founded as the South Asian Gay Association (SAGA) in 1989, it was renamed in 1991 to include lesbian members. SALGA serves Desi LGBT people from countries like Afghanistan, India, and Sri Lanka, as well as those of South Asian descent from places like Guyana and Trinidad. When SALGA applied to march in the India Day Parade in 1993, they were rejected despite having marched in 1992 after intervention by the New York City Human Rights Commission. The FIA stipulated that SALGA could only participate if its members did not carry signs stating their homosexuality, which the group refused, highlighting issues of homophobia within the community.

In response to continued exclusion from the parade, SALGA formed the South Asian Progressive Task Force in 1997 to combat discrimination. Despite being allowed to march in 2000, they were denied again in 2009, leading to silent protests along the parade route that garnered media attention. In 2010, hours before the parade, SALGA was granted permission to march again. SALGA remains active in Pride marches across New York City, advocating for visibility and acceptance within the broader community, and often organizes protest marches along the India Day Parade route with support from groups like SAKHI for South Asian Women.

Day 160: Rohwer War Relocation Center (Concentration Camp), Desha, Arkansas

📌APIA Every Day (160) - The Rohwer War Relocation Center, located in Desha County, Arkansas, operated as one of the ten American concentration camps during World War II, situated north of the Jerome Relocation Center [See Day 83]. Established on September 18, 1942, it incarcerated primarily Japanese Americans from Los Angeles and San Joaquin, California. At its peak, the camp housed approximately 8,000 people within barracks, mess halls, and guarded perimeters surrounded by barbed wire, reflecting the horrible conditions the prisoners faced. Unlike many other relocation centers where populations dwindled over time, Rohwer experienced an increase in inmates in 1944 following the closure of the Jerome camp, further complicating its operational dynamics.

Following the war, as restrictions eased, Rohwer gradually ceased operations, officially closing on November 30, 1945. Imprisoned Japanese Americans either returned to the West Coast or resettled in cities across the United States, including Chicago. The center's barracks and buildings were auctioned off and removed, with the land converted back to agricultural use for crops like cotton, soybeans, corn, and rice. Many Japanese Americans left Arkansas immediately, some returning to the West Coast to rebuild their lives, while others resettled across the United States.

Of the 168 Japanese American prisoners who tragically passed away during their time at Rohwer, most were elderly and preferred burial over cremation, resting in the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery. In 1945, two large concrete monuments were erected in the cemetery. One, adorned with floral patterns symbolic of Japanese and American cultures, honors all who died at the center, including those cremated. The second commemorates the young men from Rohwer who served in Europe and lost their lives in the U.S. Army's 100th Battalion and 442nd Combat Team. The cemetery and monuments serve as tangible reminders of Rohwer's history, and the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Day 159: Asian District, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

📌APIA Every Day (159) - The Asian District in Oklahoma City, previously known as "Little Saigon," emerged in the mid-1970s when thousands of Vietnamese refugees settled in the area following the Vietnam War. Located off Classen Blvd between NW 23rd St and NW 30th St, near Oklahoma City's Chinatown, the area was often referred to as “the Vietnamese heart” due to the memorial honoring veterans from Vietnam and their American allies in Military Park. The Vietnamese American Community of Oklahoma City raised funds to provide a statue called “Brothers in Arms” that depicts American and Vietnamese soldiers standing in solidarity. The district officially adopted the name Asian District to reflect its diverse and evolving population. Over time, the area expanded to include a variety of businesses and restaurants, attracting not only Vietnamese patrons but also the broader OKC community.

The history of Asians in Oklahoma City began before the arrival of the Vietnamese population. In the mid-nineteenth century, Chinese laborers arrived around the time of the Land Run of 1889, working in railroads, laundries, and restaurants. Early Chinese settlers lived in a small, mostly hidden "Chinatown" in downtown Oklahoma City. Their numbers peaked in the early 20th century but declined during the Great Depression. Japanese immigration to Oklahoma followed around 1900, with many working as gardeners or household staff for wealthy families. During World War II, Japanese Americans faced discrimination but were not incarcerated in Oklahoma, and the community grew post-war with new immigration laws. From the 1970s onwards, the Asian population in Oklahoma City diversified significantly. Korean immigration increased, spurred by post-Korean War policies and family reunification programs, while Vietnamese refugees arrived in large numbers, forming a vibrant community in what became known as Little Saigon.

By 2000, Vietnamese made up the largest Asian group in Oklahoma City, with significant communities of Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indians. The Asian District Cultural Association and the annual Asian Night Market Festival play a key role in maintaining cultural practices and fostering community among the diverse Asian populations. These efforts, along with the establishment of various businesses, have integrated the Asian community into Oklahoma City's broader economic and cultural landscape.

Day 158: Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, Washington

📌APIA Every Day (158) - The Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, located on the south shore of Eagle Harbor in Bainbridge Island, Washington, commemorates the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. On March 30, 1942, 227 Japanese American residents were gathered at the Eagledale Ferry Dock and sent to incarceration camps, first to Manzanar in California and later to Minidoka in Idaho. This evacuation, prompted by concerns over their proximity to naval bases during wartime, was sudden, with residents given only a few days' notice to leave their properties and belongings behind. After World War II, more than half of the Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island returned, facing significant challenges in rebuilding their lives.

The memorial is part of the Minidoka National Historic Site in Idaho and emphasizes the importance of remembering this period in American history. The central feature is a wall made of old-growth red cedar, granite, and basalt, listing the names of all 276 Japanese and Japanese Americans exiled from Bainbridge Island. The memorial project was led by the Bainbridge Japanese American Community, with significant fundraising efforts starting after its inclusion in the Minidoka National Historic Site in 2008. By 2009, $2.7 million had been raised. The first phase of the memorial, including the construction of the cedar "story wall" designed by architect Johnpaul Jones, was completed in 2011. The landscaping around the memorial features native plants, reflecting the natural environment of the area. The site was listed as a National Historic Site in 2008 with the dedication of the Departure Deck in 2021. Currently, the memorial is in its final planned phase of development with a campaign running through this year or until funding goals are met. APIAHiP will also be offering a tour on Bainbridge Island during our National Forum this upcoming September!

Day 157: Hmong Refugee Mural, Fresno, California

📌APIA Every Day (157) - The Hmong refugee mural and exhibit, part of the Hmongstory 40 project, launched in Fresno, California, in 2015, commemorating 40 years of Hmong history in America. The exhibit reflects on the turbulent experiences of the Hmong people displaced from Laos starting in 1975 who sought refuge in Thailand. It features four rooms filled with text, photos, videos, paintings, sculptures, and artifacts that narrate the Hmong experience, documenting different phases: life in Laos before the war, the Secret War in Laos, the refugee experience in Thailand, and resettlement in the United States.

At refugee camps, individuals received identity numbers for processing before being relocated to countries like the United States, France, or Australia. This history is often disconnected from the memories of second and third-generation Hmong Americans. Hmongstory 40 aimed to collect as many refugee identity photos as possible to create a large mural, measuring 10 feet by 30 feet, featuring these photos. The mural and the rest of the exhibit were displayed with the hope of inspiring and reconnecting new generations of Hmong Americans with their past. Now that we are nearing 50 years of Hmongs in America, how can we best preserve their history and culture on a local, state, and federal level?

At refugee camps, individuals received identity numbers for processing before being relocated to countries like the United States, France, or Australia. This history is often disconnected from the memories of second and third-generation Hmong Americans. Hmongstory 40 aimed to collect as many refugee identity photos as possible to create a large mural, measuring 10 feet by 30 feet, featuring these photos. The mural and the rest of the exhibit were displayed with the hope of inspiring and reconnecting new generations of Hmong Americans with their past.

Day 156: Vietnamese Martyrs Catholic Church, Biloxi, Mississippi

📌APIA Every Day (156) - The Vietnamese Martyrs Catholic Church in Biloxi, founded in 1979, serves as a significant religious and cultural center for Vietnamese Americans in Mississippi. Originally established to accommodate Vietnamese refugees following the 1975 fall of Saigon, the parish was initially named the Blessed Vietnamese Martyrs Church and was later renamed in 1989 to its current title. Since 2000, it has been under the ministry of the Vietnamese Dominican Order from Calgary, Canada. The parish is distinguished by its Our Lady of La Vang shrine, constructed in 2005, and a notable mural depicting the Holy Martyrs of Vietnam inside the church.

Beyond its religious functions, the parish is actively involved in community life. It hosts a variety of ministries and educational programs, including religious education with Vietnamese language instruction and sacramental preparation for children. Volunteerism is a cornerstone of the parish's operations, with community members contributing to administrative tasks, maintenance, and outreach efforts.

In 2005, after the devastating Hurricane Katrina, the church played a crucial role in disaster response and recovery efforts, despite severe flooding that destroyed much of its interior. Victims of the catastrophe went to the church, which provided essential items, held outdoor masses, and engaged in extensive cleanup efforts. Alongside the nearby Chua Van Duc Buddhist temple, which also provided shelter and distributed donations, the church helped anchor the community. Although many families relocated due to the high costs of rebuilding in East Biloxi, the church continued to function as a central place for worship and community support, maintaining its role as a vital cultural and religious institution. The parish's involvement extended to long-term rebuilding initiatives and advocacy for the needs of the local Vietnamese American community in Biloxi, reflecting its integral role in both spiritual and practical community support.

Day 155: International Hotel, San Francisco, California

📌APIA Every Day (155) - The International Hotel (I-Hotel), located in San Francisco's Manilatown, was a residence for elderly Filipino and Chinese immigrants. Originally covering over ten square blocks near San Francisco's Chinatown, Manilatown was home to many Filipino farmworkers, merchant marines, and service workers. In the 1960s, Financial District encroachment steadily pushed the residential Manilatown community towards "higher use" development, with the goal of demolishing the building to make way for a multi-level parking lot. On November 27, 1968, 150 elderly Filipino and Chinese tenants initiated a nine-year anti-eviction campaign in response to the plans. Represented by the United Filipino Association (UFA), tenants initially secured a lease agreement with Milton Meyer & Company on March 16, 1969. However, a suspicious arson occurred on that same day, killing three tenants and led the company to back out of the agreement, using the fire to justify demolishing the "unsafe" building. The conflict peaked on August 4, 1977, when over 400 riot police forcibly evicted the tenants during a pre-dawn raid, despite resistance from a 3,000-person human barricade. This eviction resulted in significant public outcry and the eventual demolition of the International Hotel in 1979.

The effort to preserve the I-Hotel site continued post-eviction, led by the International Hotel Citizens Advisory Committee (IHCAC), formed by Mayor Dianne Feinstein. The committee worked to ensure that the site would be used for low-income housing. Although the I-Hotel's owner initially intended to demolish the building for commercial use, community opposition and volunteer efforts delayed the eviction and led to temporary lease agreements. Despite ownership changes and legal battles, the IHCAC secured a zoning ordinance in 1982 that mandated housing on the site, preventing commercial redevelopment.

Between 1983 and 2004, various development negotiations occurred, culminating in the sale of the I-Hotel site to the Catholic Church in 1998. This sale enabled the construction of new low-income housing and the establishment of St. Mary's Chinese Schools and Catholic Center. The new I-Hotel, which opened on August 26, 2005, provides 104 units of affordable housing for elderly residents, continuing the legacy of community support. The Manilatown Heritage Foundation and associated organizations have maintained cultural and social services for the residents, reflecting a commitment to preserving the history and purpose of the original I-Hotel. In 1977, the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Day 154: Polly Bemis House, Riggins, Idaho

📌APIA Every Day (154) - The Polly Bemis House, located in Riggins, Idaho, served as the home of Charles and Polly Bemis during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Polly Bemis, a Chinese woman brought to the United States as an indentured servant, became a significant figure due to her resilience and compassion. Sold by her parents because of drought and famine, Polly arrived in Warren, Idaho, in 1872. She left her Chinese owner and later met Charlie Bemis, whom she nursed back to health after a severe injury.

Chinese miners began arriving in Idaho almost as early as white miners, and by 1870, they constituted about half of the state's population. However, during the 1890s, white suppression forced most Chinese immigrants to relocate to Chinatowns on the West Coast. As a result, Polly was the only Chinese woman in Warren at the time and managed Charlie's boarding house. The couple married in 1893, securing Polly's U.S. citizenship, and they established a homestead known as "Polly’s Place," which became a sanctuary for locals and travelers. The Bemis’ initially established their residence on a mining claim rather than a homestead, highlighting the unique nature of their settlement.

In 1922, the original Bemis home was gutted by a fire, likely caused by an overheated woodstove. Shortly after this incident, Charles Bemis, who had been suffering from a lung ailment, passed away. Polly Bemis, with the assistance of neighbors Peter Klinkhammer and Charlie Shepp, reconstructed a new house on the same site in 1923. She continued to live there until 1933, except for a brief stay in Warren, Idaho. Polly's later years saw her relocating to Grangeville, Idaho, where she died soon after. Currently part of a 26-acre non-profit ranch, the Polly Bemis House is a preserved historical site, while the nearby Klinkhammer and Shepp residence has been converted into the Shepp Ranch guest facility. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in March 1988.

Day 153: Quincy Grammar School, Boston, Massachusetts

📌APIA Every Day (153) - The Quincy Grammar School, opened in 1848, was a model public school conceived by renowned educator Horace Mann. Designed by architect Gridley J.F. Bryant, the building featured classrooms for individual teachers and separated students by grade, which were progressive ideas at the time.

By the late 19th century, the Quincy Grammar School offered evening classes for the immigrants of South Cove and became a key institution for educating immigrant children, including a growing number of Chinese students. The first Chinese student enrolled in 1891, and the trend of Chinese enrollment increased significantly after World War II with the arrival of many Chinese families. By the mid-20th century, more than 90% of the students were Chinese American, making the Quincy Grammar School the primary educational facility for Chinese American children in Chinatown.

The school closed in 1976, and in 1983, it was acquired by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA). The CCBA transformed the building into a cultural center, providing social services and cultural programs for the community. The Quincy School is now recognized for its role in the history of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans in Boston and its progressive architectural design. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in June 2017.

Day 152: Refugee Processing Center at Camp Pendleton, San Diego, California

📌APIA Every Day (152) - Camp Pendleton, situated within a Marine base in San Diego, California, was designated as one of four refugee centers for Vietnamese refugees following the Fall of Saigon in April 1975 [See days 104 and 121 for info on other refugee centers]. Within just 36 hours, military personnel prepared the camp by erecting tents, setting up cots, and stocking essential supplies to accommodate over 100,000 evacuees. Upon arrival, refugees underwent processing, which included receiving inoculations, basic comfort packs containing toiletries, and military jackets for warmth. As part of "Operation New Life," Camp Pendleton played a crucial role in resettling Vietnamese refugees, ultimately hosting nearly 20,000 individuals at its peak. Life at the camp was characterized by the refugees' efforts to adapt to their new environment amidst the challenges of starting over and processing the trauma from their homeland. Over time, as refugees found sponsors and resettlement opportunities across the United States, they gradually moved out of Camp Pendleton.

Community support from organizations like the Red Cross and local churches played a significant role in aiding the resettlement efforts. Despite the initial challenges, many refugees managed to adapt swiftly, learning English and participating in various activities offered at the camp. Camp Pendleton's role marked a significant chapter in the establishment of the Vietnamese American community, particularly in areas like Orange County and San Jose.

Day 151: Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park, Kailua Kona, Hawai’i

📌APIA Every Day (151) - Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park, located on the west coast of the Island of Hawai‘i, was established in 1978 to preserve and interpret traditional native Hawaiian activities and culture. Covering approximately 1,200 acres, the park includes the Honokōhau Settlement, a National Historic Landmark. The creation of the park was guided by the Spirit Report, developed by the Honokohau Study Advisory Commission in 1972, which remains the primary document for the park's management. The park encompasses coastal portions of five ahupua‘a, traditional Hawaiian land divisions, preserving a historically significant Hawaiian community.

The park features numerous archaeological and cultural sites such as loko i‘a (fishponds and a fishtrap), kahua (house site platforms), ki‘i pōhaku (petroglyphs), heiau (temples), graves, and historic trails. These elements illustrate the advanced fishing and agricultural practices of the Native Hawaiians who adapted to the region's harsh environment. The Spirit Report emphasizes that these resources represent a comprehensive historical Hawaiian community, showcasing the importance of preserving and demonstrating traditional Hawaiian skills and knowledge.

Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park also supports diverse native wildlife, including endangered species such as the ae‘o (Hawaiian stilt) and ‘alae ke‘oke‘o (Hawaiian coot) at the ‘Aimakapā Fishpond. The park's ecosystems provide habitats for migratory waterfowl, juvenile honu (Hawaiian green sea turtles), and occasionally the ‘īlioholoikauaua (Hawaiian monk seal). The park’s offshore waters are rich in marine life, offering opportunities for visitors to observe vibrant coral and fish species. Serving both as a cultural heritage site and a natural habitat, the park provides insight into Native Hawaiian culture.

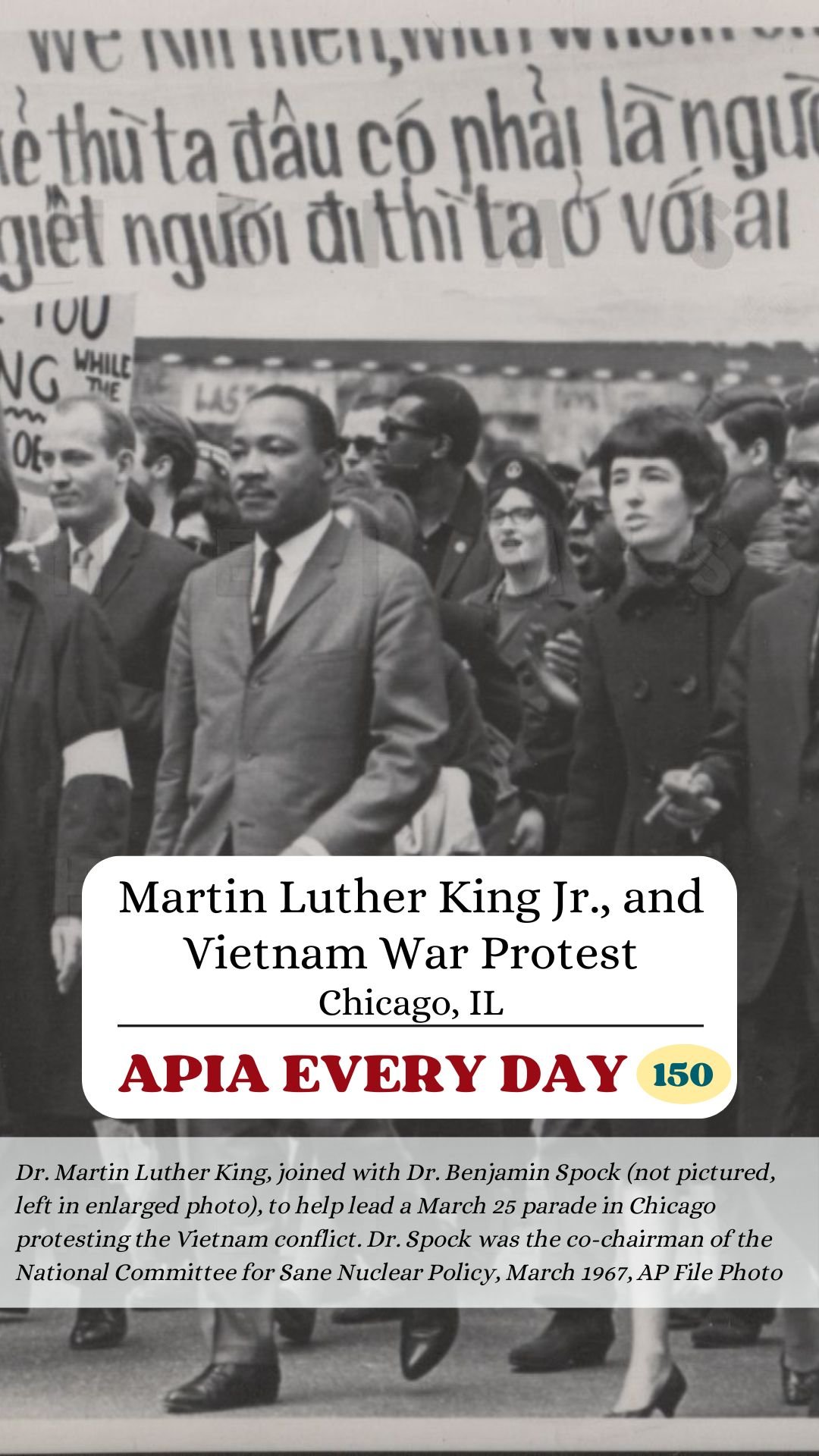

Day 150: Martin Luther King Jr., and Vietnam War Protest, Chicago, Illinois

📌APIA Every Day (150) - Martin Luther King Jr.'s involvement in the anti-Vietnam War movement marked a significant shift in his activism, reflecting broader concerns about social justice and the war's impact on civil rights. Initially cautious in his criticism to maintain his relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson, King began publicly condemning the war by late 1965, advocating for peaceful solutions and highlighting its moral implications. He led his first Vietnam War protest in Chicago, Illinois on March 25, 1967, alongside 5000 anti-war advocates and leaders such as Dr. Benjamin Spock, the co-chairman of the National Committee for Sane Nuclear Policy. Following the protest, his pivotal speech, "Beyond Vietnam," delivered on April 4th, underscored his belief that the war diverted resources from addressing domestic poverty and racial inequality, stating, "The bombs in Vietnam explode at home—they destroy the dream and possibility for a decent America."

Amidst King's anti-war activism, African Americans faced heightened challenges in the military, experiencing systemic racism despite official desegregation. Policies like Project 100,000 disproportionately drafted Black soldiers, who encountered racism on military bases, including Confederate symbols and cultural restrictions. Racial tensions boiled over into conflicts such as race riots on ships like the USS Kitty Hawk and USS Constellation. Despite some reforms introduced during the war, many Black troops continued to face discrimination.

King's stance against the Vietnam War aligned with broader African American opposition, echoing sentiments from leaders like Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. This solidarity was rooted in a rejection of racial injustices inherent in the war effort, with protesters arguing that Black Americans should not fight against Vietnamese people striving for their own freedom but rather against the racism perpetuated by the U.S. military and society. This period exemplified a convergence of civil rights and anti-war movements, reflecting a shared struggle against systemic racism and injustice both at home and abroad.

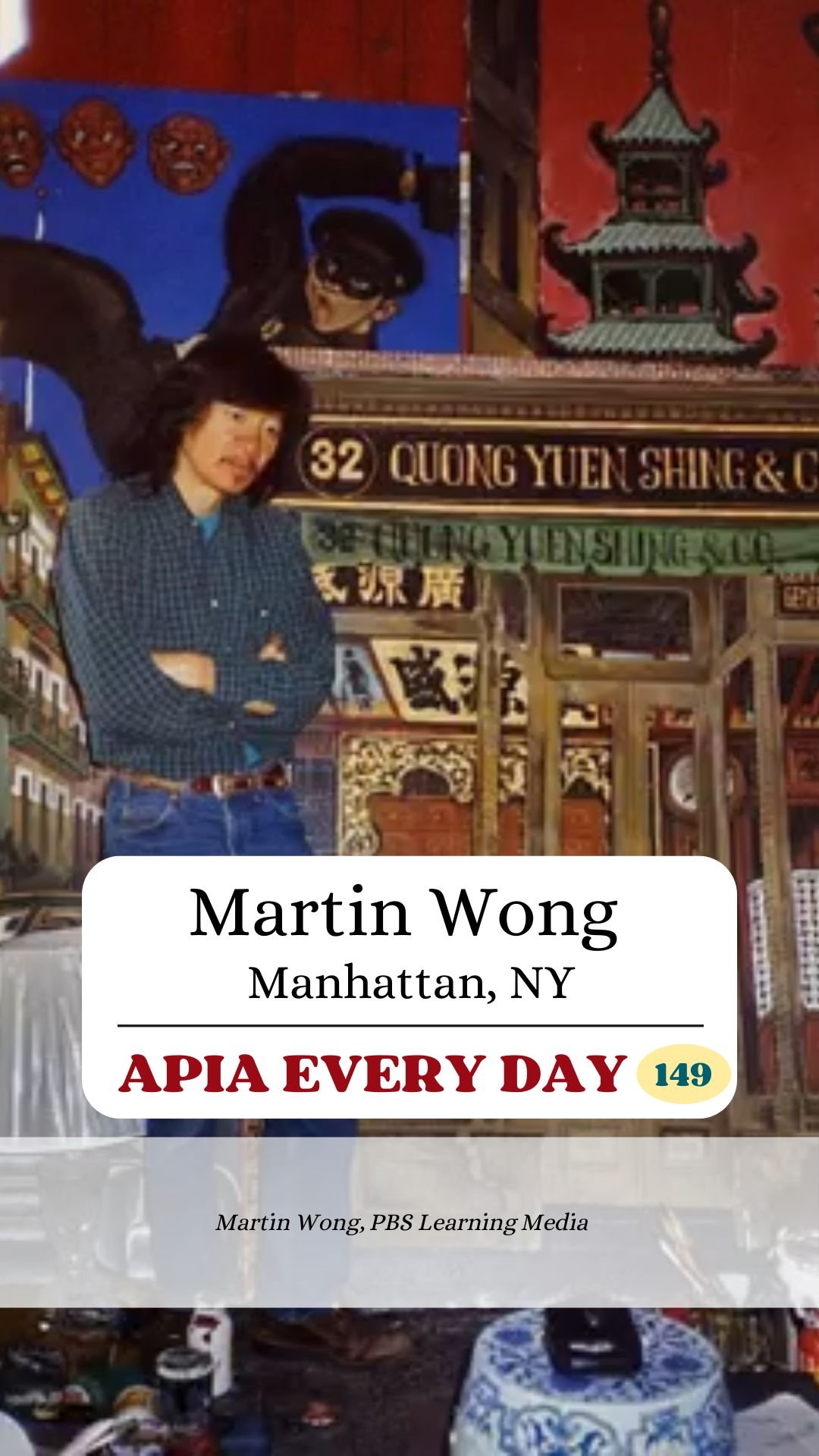

Day 149: Martin Wong, Manhattan, New York

📌APIA Every Day (149) - Martin Wong was a Chinese American artist known for his distinctive representational imagery, which encompassed urban environments, Chinatown’s history and stereotypes, and homoerotic content. After moving to the Lower East Side of New York City in 1978, Wong settled at 141 Ridge Street in 1982, where he lived and worked. His art drew heavily from his surroundings in San Francisco’s Chinatown, where he grew up, and Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Chinatown. Wong's paintings frequently addressed the displacement of residents due to gentrification, with recurring themes of brickwork and American Sign Language.

Wong was a prominent figure in the 1980s and early 1990s downtown arts scene, forming friendships with artists such as David Wojnarowicz and Keith Haring. His significant collaboration with Miguel Piñero, a writer and co-founder of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, influenced his connection to the Puerto Rican community in the Lower East Side. Wong and Piñero collaborated on several artistic projects and briefly lived together. Wong’s notable painting "Attorney Street (Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero)" reflects this period and was later acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition to his paintings, Wong was an early collector of graffiti art, amassing a substantial collection of graffiti works and publications throughout the 1980s. In 1989, he co-founded the Museum of American Graffiti in the East Village, though it was short-lived. Diagnosed with AIDS, Wong returned to San Francisco in 1994 to be with his parents and subsequently donated his graffiti collection to the Museum of the City of New York. Wong passed away in 1999 at the age of 53. His work is held in major New York institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New-York Historical Society. His legacy has been honored with retrospectives at the New Museum in 1998 and the Bronx Museum in 2015.

Day 148: Francisco Q. Sanchez Elementary School, Humåtak, Guam

📌APIA Every Day (148) - The Francisco Q. Sanchez Elementary School, located in Humåtak, Guam, served as the only educational institution in the village. Built in 1953 by internationally known architect Richard Neutra, the school was named after its first principal, Francisco Q. Sanchez, an early pioneer of historic and cultural preservation from Humåtak. Unfortunately, the school closed in 2011 due to financial constraints, marking a significant loss for the community.

Neutra, who studied under prominent Modernists in Vienna and worked with architects like Frank Lloyd Wright in the United States, incorporated modern materials and techniques into the school's design. The structure features two one-story wings with views of Humåtak Bay and the island's flora and fauna, reflecting Neutra's philosophy of "biorealism," which emphasizes harmonizing human structures with nature. The school was part of an urban Master Plan under Governor Carleton Skinner, although the plan was later abolished, making F.Q. Sanchez Elementary the only intact building from that initiative.

The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998 and later nominated by the Guam Preservation Trust as one of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places for 2022. This designation, supported by the Guam Preservation Trust, Humåtak Mayor Johnny Quinata, Governor of Guam Lou Leon Guerrero, and other officials, brought national attention and preservation efforts to the site. Consequently, Public Law 36-82, signed in March 2022, allocated $3.5 million for the rehabilitation of the school. This past March, Mes Chamoru, the month to celebrate Chamoru history and culture, kicked off the building’s reconstruction. Several future uses for the site are being considered, including a charter school, a senior citizen center, a museum and café, or housing the Humåtak Mayor’s office. Ultimately, the local community will have input on the school’s future.

Day 147: Republic Cafe, Salinas, California

📌APIA Every Day (147) - The Republic Cafe, established in 1942 by Wallace (Wally) Ahyte and Bow Chin, served as a significant gathering place in Salinas, California's Chinatown. The restaurant, which could accommodate up to 150 people, was central to the community, hosting events like Lunar New Year celebrations, weddings, and banquets. It became a key cultural hub for various ethnic groups, including Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican, and African American residents.

Salinas's Chinatown began to form in the 1860s with the arrival of Chinese immigrants. By the early 20th century, Japanese laborers joined the community, diversifying the demographic. The Chinese merchant class grew in the 1920s, establishing businesses and cultural spaces to serve the broader community. The Ahyte family, particularly involved in this development, contributed significantly by opening and managing various enterprises, including the Republic Cafe.

From the late 1950s, economic decline affected Salinas's Chinatown, accelerated by the Federal Urban Renewal Program, which led to the demolition of many buildings deemed unsafe. The Republic Cafe continued to operate until 1988, one of the last businesses to close in the district. Although it has been vacant since its closure and suffered a fire in 2022, there are plans to convert it into a cultural center and museum to honor the history of Salinas's Chinatown. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Day 146: Bhutanese Community, Fargo, North Dakota

📌APIA Every Day (146) -The Bhutanese community's presence in Fargo, North Dakota, began over a decade ago as part of a larger refugee resettlement program. Bhutanese refugees, of Nepali descent, were expelled from Bhutan after being expelled from their homeland due to ethnic and political tensions in the early 1990s. They lived in camps in Nepal without citizenship or integration opportunities; these issues led the the UN began resettling them in the U.S. and other countries in 2007. By 2013, over 66,000 had moved to the U.S., forming communities in states like Pennsylvania, Texas, Georgia, California, and North Dakota, where about 70% live in Fargo.

Upon arrival in Fargo, the Bhutanese community quickly began to establish roots. They set up homes and started businesses that catered to both their cultural needs and the wider community. Community organizations have played a crucial role in the integration and support of the Bhutanese in Fargo. These organizations help with job training, language classes, and cultural events, fostering a sense of community and belonging. United Chinese Americans Fargo-Moorhead, although primarily serving Chinese Americans, exemplifies the type of support network that benefits all Asian communities in the area. These groups have been instrumental in helping the Bhutanese navigate their new environment and maintain their cultural heritage.

Despite facing occasional racism and microaggressions, the Bhutanese community in Fargo has generally found the city to be a welcoming place. Instances of violent hate crimes are relatively rare compared to other parts of the country. Many Bhutanese have taken advantage of Fargo's affordable housing and job opportunities, particularly in sectors like tech, medical, and manufacturing. This combination of economic opportunity and community support has allowed the Bhutanese in Fargo to not only survive but thrive, contributing significantly to the local economy and cultural landscape.

Day 145: Wat Thai, Silver Spring, Maryland

📌APIA Every Day (145) - Wat Thai, a Buddhist temple located in Silver Springs, Maryland, was founded in 1974 by the Thai Buddhist community known as "The Buddhist Association in Washington DC” and is the second Thai temple established in the U.S., following the temple established in Los Angeles. Initially established in a small house in Washington DC, the community wrote to Wat Mahathat in Bangkok, requesting monks to serve the newly formed temple. The monks arrived on July 4, 1974, a date that coincided with both American Independence Day and Asalaha Bucha Day, an important Thai Buddhist festival. This beginning symbolized the foundation of a new Thai Buddhist community in the United States. Over time, Wat Thai has relocated to its current, more spacious location in Silver Spring, reflecting its growth and the increasing number of congregants.

Under the leadership of its second and current abbot, Phra Maha Surasak, Wat Thai has expanded significantly. The Thai initially had two monks; now, the temple supports ten fully ordained monks and serves over 2,200 families and 37,000 individuals in the greater Washington DC area. The temple offers various services and activities rooted in Thai Theravada Buddhist traditions, including regular meditation sessions, Dhamma discussions, and bimonthly workshops in both Thai and English. Phra Maha Surasak, also known as Luang Ta Chi, is a prolific writer who educates others through short stories about the Dhamma, making Buddhist teachings accessible to a wider audience.

Wat Thai plays a crucial role in promoting Thai culture and Buddhist practices within both the Thai immigrant community and the broader public. The temple hosts significant cultural events such as the Kathina Ceremony and Songkran (Thai New Year), which attract not only Thai Buddhists but also people from diverse backgrounds interested in Thai traditions. Additionally, Wat Thai offers Thai language courses and traditional music and dance classes, fostering a deeper appreciation and understanding of Thai culture.

Day 144: Community United Methodist Church, Queens, New York

📌APIA Every Day (144) -The Community United Methodist Church in Jackson Heights, Queens, established in the early 20th century, has become a significant community hub, especially under the leadership of Reverend Austin Armitstead (1974-1995), who defended gay congregants against anti-gay protestors. The church offers multi-language ministries and meeting spaces for diverse community groups, reflecting the neighborhood's ethnic diversity and LGBT presence. In 1990, the church hosted a groundbreaking candidates' night on LGBT issues and HIV/AIDS, which led to the formation of Queens Gays and Lesbians United (Q-GLU) in 1991 by Ed Sedarbaum and Susan Caust. Q-GLU, formed in response to local events like the gay-bias murder of Julio Rivera, advocated for LGBT issues specific to Queens, organized regular meetings at the church, and collaborated with the Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project to improve police relations with the LGBT community.

The church also served as a venue for significant events such as the Interfaith AIDS Memorial Service on June 5, 1999. This event, co-sponsored by various organizations including the Asian/Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV & AIDS (APICHA), featured clergy from multiple faiths and displayed panels from the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. APICHA was founded in 1989 by a group of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans concerned about HIV/AIDS rates within their communities and is dedicated to combating discrimination, preventing HIV transmission, and providing care for those living with HIV/AIDS. APICHA offers a range of services including primary and specialty HIV care, bilingual case management, and HIV prevention education. Notably, APICHA convinced the CDC to separately list "Asians and Pacific Islanders" from "Alaskan Natives and American Indians."

The Community United Methodist Church has played a pivotal role in fostering community solidarity and advocating for LGBT rights in Jackson Heights, involving various ethnic and minority groups, including Asian and Pacific Islander Americans, through collaborations like those with APICHA.